New Flora

New Flora: On Blossoms and Metamorphoses in the 1920s

Black days of winter all were through

The blossoms came and they brought you

Clouds left the sky

And I knew the reason why

They made way for you and the blossom.

—Nick Drake, “Blossom”

Floral motifs were very popular in the 1920s. Blossoms featured on summer dresses, and flowers and leaves were dominant elements in fashion illustrations—the vegetal designs that pervaded these advertisements clearly aimed at seducing consumers. While this observation might not initially seem all that exceptional, since floral fabrics are ubiquitous today, it is worth taking a careful look at the flower euphoria of the Weimar Republic, as it was a period in which, at least in the cities, gender roles became more nuanced and liberated than ever before. The disintegration of the categorical separation of female and male was expressed nowhere more distinctly than in fashion—in hairstyles, makeup, and attitudes as much as in clothing. The meaning of blossoms in patterns, décor, and furnishings was one of ambivalence—between the genders, between skin and textiles, between flora and flappers. The eighteenth-century Swedish botanist Carolus Linnaeus helps put this shift into a historical context: while his descriptions of the plant kingdom remain valid today, they were shaped by his view of gender and the world. On an expedition through the moors of Lapland in 1732, Linnaeus came across a flower that he would later name Andromeda after the figure from Greek mythology, describing it as follows: “I doubt that a painter would be able to transfer such grace to an image of the Virgin Mary or lend such beauty to her cheeks.”[1] The flower as a virgin, a woman, or both is a motif he frequently used in his botanical and scientific writings, which have since been published into many languages, although, in fact, most flowers are actually hermaphrodites.[2]

New Flora and the New Woman

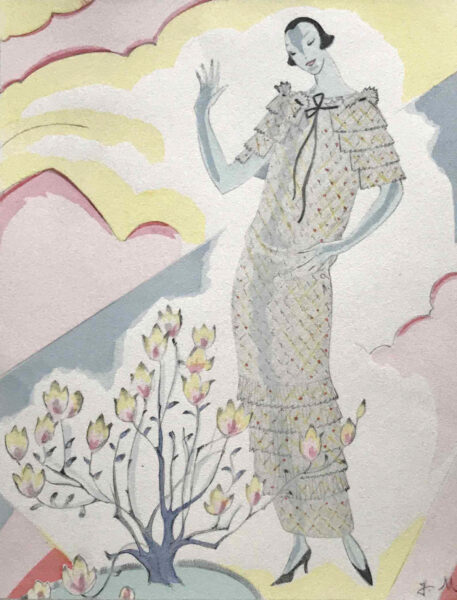

The 1920s is considered the decade in which the New Woman was invented. The Wilhelmine Period’s conservative image of women underwent a transformation after World War I, and new realms of freedom emerged in the Weimar Republic, especially in urban settings. More women were working, finding employment as secretaries, train conductors, and sculptors, and they frequented cafés and cinemas without male chaperones.[3] This emancipation extended to clothing and appearance: hemlines rose, corsets were replaced by elasticized girdles or completely abandoned, and hairstyles became shorter. These visual changes were often described in masculine terms, such as the pageboy hairdo (known as Bubikopf in German) or the garçonne (“boy” in French but with a feminine suffix), used to describe an androgynous woman fitted out with masculine accessories like a necktie and monocle.[4] The umbrella term New Woman suggested this radical turn from the past era as an “optimistic social fantasy.”[5] However, it is astounding how traditional attributes were persistently maintained, particularly women’s presumed proximity to nature; for example, the perception of femininity as elemental and close to nature is manifested in the many flowers and blooms that decorated the fabrics of summer dresses and scarves as well as in the scenic backdrops used in fashion illustrations and photographs.[6] Floral motifs set the tone for the small fashion vignettes in daily newspapers as much as for the artistically ambitious pochoir prints in the Berlin fashion magazine Styl,which was published between 1922 and 1924. German painter and illustrator Jeanne Mammen, for example, showcases a summer dress from the fashion boutique Gerson on a model elegantly posed in front of a magnolia tree.[7] Although these fashion plates might appear contrived and affected, they combine nature and femininity as an inseparable unit.

The New Woman is also always a new Flora, the Roman goddess of blossoming plants and the allegorical embodiment of spring, the season that ushers in the new.[8] German artist Otto Dix’s portrait of his wife, Martha, wearing an ornamental, vegetal-patterned dress and holding the funnel-shaped flower of a trumpet vine, shows her firmly rooted in this history of associating women with nature—although her knee-length dress and short hairstyle, with its precisely cut bangs, are unquestionably datable to the 1920s. Even in August Sander’s photographic portrait of Anneli Strohal, a secretary at Cologne’s Westdeutscher Rundfunk radio station, her visually radical and contemporary look remains connected to conventional images of women through a floral motif: Strohal wears her hair short and smokes a cigarette, while a high-necked, tight-fitting dress with floral embroidery extends over her belly and lap (areas associated with reproduction) and down to her knees. In fashion, patterns had their own codes: geometric designs, checks, or stripes were considered “masculine,” while floral decoration was considered “feminine.”[9]

Gender-Fluid Identities

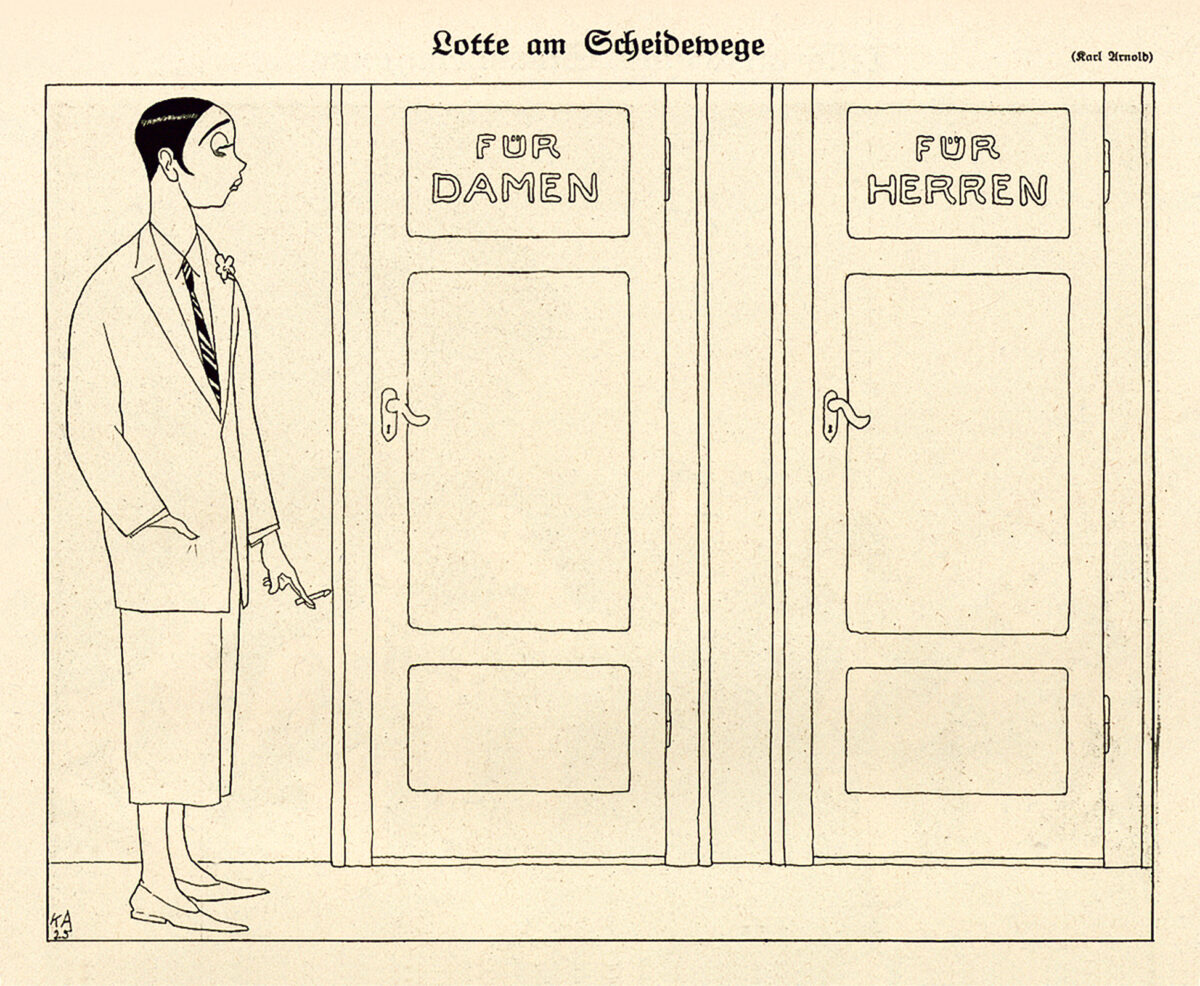

Texts and satirical images in the 1920s warned against the “masculinization” of women, predicting the possible demise of humanity through the depiction of horror scenarios where women could no longer reproduce. In Lotte am Scheidewege (Lotte at the crossroads), Karl Arnold’s 1925 illustration for the journal Simplicissimus, a woman is unable to decide between women’s and men’s clothing. Masculinized and magnificent,[10] New Women wore suits or sleek ensembles accessorized with ties, monocles, canes, and cigarettes.[11] Flowers made only small yet spectacular appearances, on a lapel, for example, as in the case of Lotte. Dressed in this way, the garçonne staged herself as a gallant or beau and as a potential lesbian.[12]

This potentiality was a central transitory concept for gender-fluid identities in the 1920s, as it remained vague as to whether the garçonne’s appearance, pose, and stance were an admittance of homosexuality or merely a fashion statement. Alfred Eisenstaedt’s 1928 photograph of actress Marlene Dietrich portrays her wearing a tuxedo and a top hat. Dietrich’s left hand is in her trouser pocket, and the large white flower pinned to her lapel can be read as a self-assured and flamboyant nod to Flora. In her study Anzug und Eros (Suit and Eros), Anne Hollander describeshow men in nineteenth-century paintings were dressed in dark suits and juxtaposed with the light and colors of nature: “Such works emphasize the moral and intellectual superiority of men in contrast with the brilliant lack of discipline in nature.”[13] Dietrich’s appropriation of the suit—with the distance from nature it implies—and her accessory of a conspicuously large flower blurs the hermetic distinctions between nature/culture and male/female.

Transformation and constant self-renewal are recurring motifs in the visual arts and literature. In Kleine Daphne (Small Daphne, 1918), the sculptor Renée Sintenis captures the moment in which the nymph is transformed into a laurel tree so she can escape the sexually motivated advances of Apollo. In 1934, Sintenis illustrated the German edition of Virginia Woolf’s book Flush: A Biography for the publisher S. Fischer. Woolf’s novel Orlando: A Biography,whichhad been published in German by Insel-Verlag in Leipzig in 1929, describes the life and development of Orlando over a period of three hundred years beginning in the sixteenth century, including the protagonist’s overnight transformation from a man into a woman.

The Danish painter Lili Elbe, a contemporary of Woolf’s fictional Orlando, was a transgender woman who underwent gender-affirming surgery in 1930. Photographs show Elbe in floral summer dresses that stress the right to insert oneself into a history of fashion that is decidedly feminine—to become Flora. Flowers can also be a means of accentuating a part of one’s femininity, as in masculine self-fashioning. A series of photographs by Man Ray show the artist Marcel Duchamp transformed into his alter ego Rrose Sélavy. A dress, wig, hat, jewelry, and a repertoire of gestures that can only be read as specifically feminine contribute to his transformation. Ensconced in the floral name Rrose Sélavy are various possible interpretations: the rose, the color pink, eros as an anagram of Rrose, and c’est la vie (that’s life) as a homonym of Sélavy.[14]

Flowers of the Skin

In addition to being found on the “second skin” of fashion, flowers are also a motif on actual skin, literally, in the form of tattoos. As the Austrian curator Beate Ermacora argues, skin is frequently read as a “system of symbols” and interpreted as “representative of the ego, if not the ego itself.”[15] Tattoos can thus be understood as a permanent form of self-expression that is closely linked to the wearer. A person’s life story is manifested on their skin.

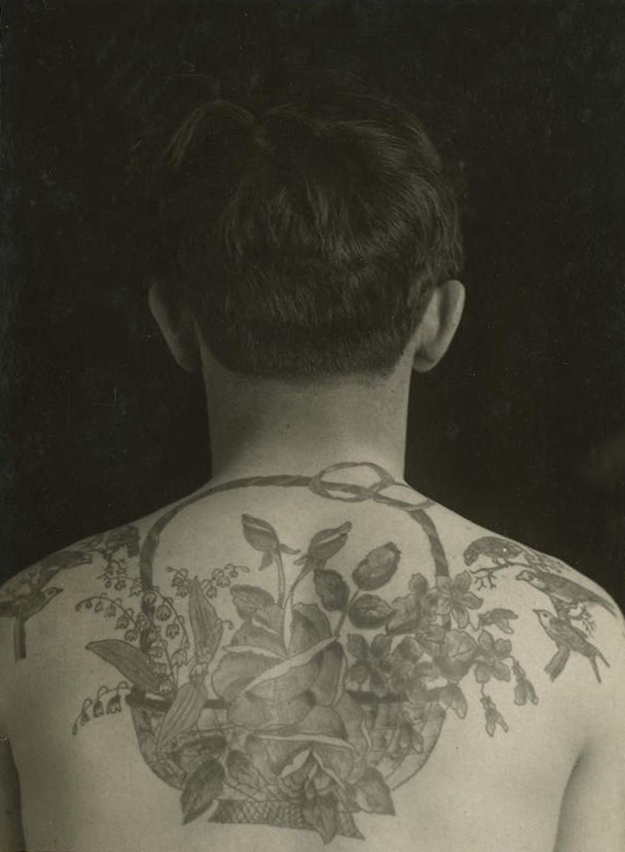

In the early twentieth century in the West, visible tattoos were associated with a specific milieu of sailors, actors, sex workers, and prisoners. In 1908, architect Adolf Loos wrote: “Modern people who have tattoos are criminals or degenerates. There are prisons in which eighty percent of the prisoners have tattoos.”[16] Christian Warlich contributed to the professionalization of tattoos by establishing a tattoo parlor in a pub in the Saint Pauli district of Hamburg in 1919. His pattern book contains tattoos that incorporate plants in numerous ways: a woman emerging from a red flower, hearts entwined with flowering vines dedicated to “Mother,” and a female nude on grapevines.[17] Photographs also document many tattoos by Warlich featuring floral motifs, including large-format arrangements, such as a basket of flowers with birds perched on far-extending branches, which was tattooed onto a man’s shoulder blade. When it takes the generous form of a consolidated whole-body tattoo, the floral motif becomes a flowered suit or fleurs de peau (flowers of the skin).[18]

The popularity of the flower motif in the 1920s cannot simply be reduced to an expression of traditional femininity. The great demand for floral designs in fashion or on the skin can also be understood as the expression of a confident self-fashioning used to overcome identities and genders that were understood as binary. It is noteworthy that flowers, a product of spring and therefore comprehended in cycles, were permanently inscribed on the body. While blossoms may develop into fruit in the summer, autumn marks the end of a period of flowering that begins again the following year. This cycle of growth and decay inspired musician Nick Drake’s song “Blossom” in the early 1970s, in which he links unrequited love with the season of spring and flowers: “When spring returns I’ll look again / To find another blossom friend / Until I do / Find something new / I’ll just think of you and the blossom.”[19] However, in the form of tattoos, flowers can be preserved; using the skin as a canvas, the flower becomes one with the person.[20]

- ↑ Carl von Linné, cited in Isabel Kranz, “Zur Poetik der Pflanzennamen der Botanik: Carl von Linné,” Poetica 50 (2019): 104.

- ↑ See Londa Schiebinger, Nature’s Body: Gender in the Making of Modern Science (New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press, 2004), 21.

- ↑ See the picture spread “Frauen, die ihr Geld selbst verdienen” in Moden-Spiegel 42 (1926), which shows women working as a laboratory technician, a writer, a sculptor, and a painter. See also Burcu Dogramaci, “‘Frauen, die ihr Geld selbst verdienen’: Lieselotte Friedlaender, der ‘Moden-Spiegel’ und das Bild der großstädtischen Frau,” in “Garçonnes à la mode in Berlin und Paris der zwanziger Jahre,” ed. Stephanie Bung and Margarete Zimmermann, Querelles: Jahrbuch für Frauen- und Geschlechterforschung 11 (Göttingen: Wallstein, 2006), 54–56.

- ↑ See Susanne Meyer-Büser, Bubikopf und Gretchenzopf: Die Frau der zwanziger Jahre, exh. cat., Museum für Kunst und Gewerbe, Hamburg (Heidelberg: Edition Braus, 1995); Annegret Pelz, “City Girls im Büro: Schreibkräfte mit Bubikopf,” in City Girls: Bubiköpfe & Blaustrümpfe in den 1920er Jahren, ed. Julia Freytag and Alexandra Tacke (Cologne: Böhlau, 2011), 35–54.

- ↑ Katharina Sykora, “Die Neue Frau: Ein Alltagsmythos der Zwanziger Jahre,” in Die Neue Frau: Herausforderung für die Bildmedien der Zwanziger Jahre, ed. Sykora et al. (Marburg: Jonas Verlag, 1993), 9–24. See also Petra Bock, “Zwischen den Zeiten—Neue Frauen und die Weimarer Republik,” in Neue Frauen zwischen den Zeiten, ed. Bock and Katja Koblitz (Berlin: Edition Hentrich, 1995), 14–37.

- ↑ See Gesa Kessemeier, Sportlich, sachlich, männlich: Das Bild der “Neuen Frau” in den Zwanziger Jahren: Zur Konstruktion geschlechtsspezifischer Mode der Jahre 1920 bis 1929 (Dortmund: edition ebersbach, 2000), especially the chapter “Frau und Natur,” 144–49.

- ↑ On fashion illustrations of the 1920s in Styl and other magazines, see Burcu Dogramaci, “Fenster zur Welt—Künstlerische Modegraphik der Weimarer Republik aus dem Bestand der Kunstbibliothek zu Berlin,” in Jahrbuch der Berliner Museen 2003 (Berlin: Gebr. Mann Verlag, 2004), 201–33.

- ↑ Labor RDK Online, s.v. “Flora,” by Julius S. Held and Ulrich Rehm (2001). Online: www.rdklabor.de/w/?oldid=89043.

- ↑ See Kessemeier, Sportlich, sachlich, männlich, 237–40.

- ↑ The German word for “magnificent,” herrlich, also contains the word Herr (German for Mr.).

- ↑ See captions and texts from 1920s fashion magazines cited in Kessemeier, Sportlich, sachlich, männlich, 206.

- ↑ Garçonne was also the title of a Berlin magazine published between 1930 and 1932 as the successor of the magazine Frauenliebe. See Petra Schlierkamp, “Die Garçonne,” in Eldorado: Homosexuelle Frauen und Männer in Berlin 1850–1950: Geschichte, Alltag und Kultur (Berlin: Edition Hentrich, 1992), 169–79.

- ↑ Anne Hollander, Anzug und Eros: Eine Geschichte der modernen Kleidung (Berlin: Berlin Verlag, 1995), 239.

- ↑ See, among others, Deborah Johnson, “R(r)ose Sélavy as Man Ray: Reconsidering the Alter Ego of Marcel Duchamp,” Art Journal 72, no. 1 (2013), 80–94.

- ↑ Beate Ermacora, “Doppelt Haut,” in Doppelt Haut, exh. cat., Kunsthalle zu Kiel (Kiel, 1996), 7.

- ↑ Adolf Loos, “Ornament und Verbrechen” (1908), in Programme und Manifeste zur Architektur des 20. Jahrhunderts, ed. Ulrich Conrads (Gütersloh: Bertelsmann, 1964), 15.

- ↑ See the comprehensive publication Christian Warlich—Tattoo Flash Book: Vorlagealbum des Königs der Tätowierer, ed. Ole Wittmann (Munich, London, and New York: Prestel, 2019). Nature motifs can also be identified in the virtual tour of the exhibition Tattoo-Legenden: Christian Warlich auf St. Pauli, Museum für Hamburgische Geschichte, 2019. Online: https://my.matterport.com/show/?m=fv4HDgwSFmu.

- ↑ Borrowed from the book titled Fleurs de peau, which features color photographs taken of tattooed prisoners in Lyon by a prison doctor in the 1930s. Gérard Lévy and Serge Bramly, Fleurs de peau: Bilder auf der Haut (Munich: Gina Keyahoff Verlag, 1999).

- ↑ Nick Drake’s “Blossom” is available on YouTube: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=2sy7ik6qM90.

- ↑ Christoph Geissmar-Brandi describes the epidermis in its various interpretations as “leather, parchment, living skin, film, canvas, . . . and not least as paper.” Christoph Geissmar-Brandi, “Gesichter der Haut—Einleitung,” in Gesichter der Haut, ed. Geissmar-Brandi et al. (Frankfurt am Main and Basel: Stroemfeld/Nexus, 2002), 11.