Exhibition

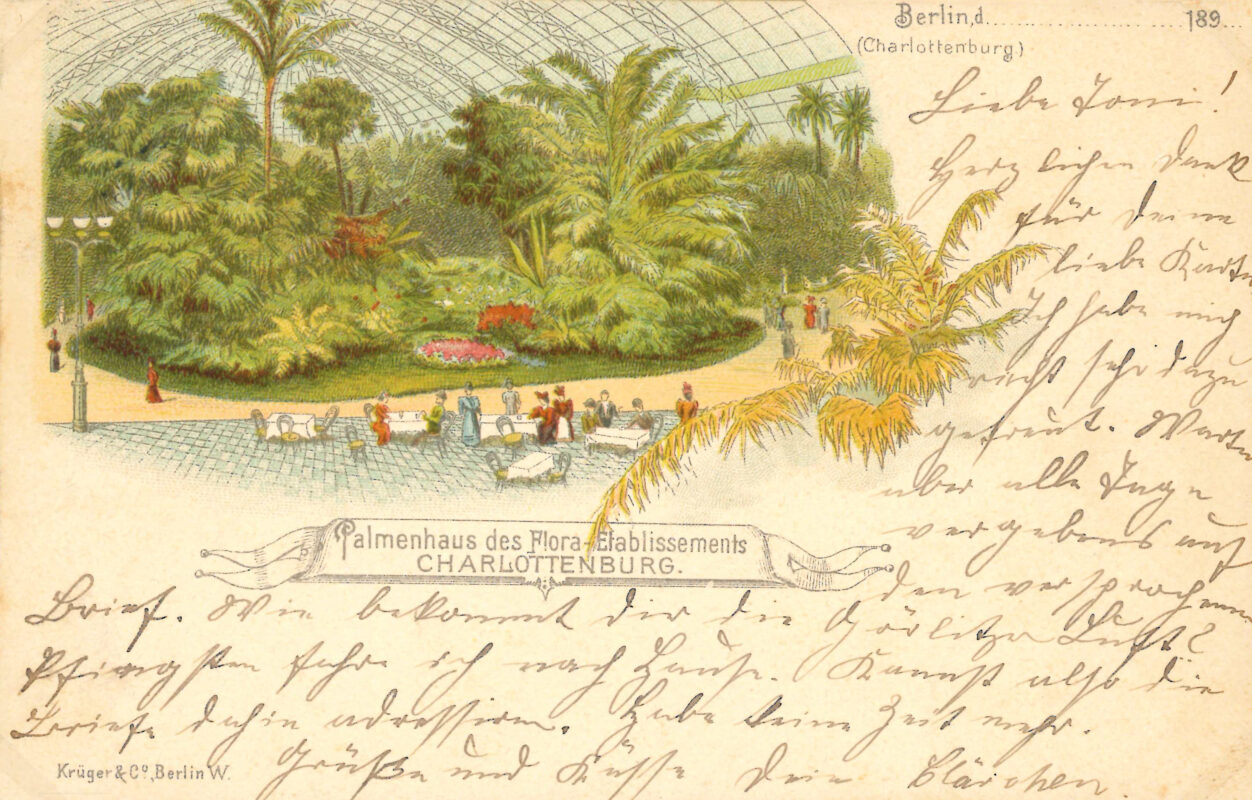

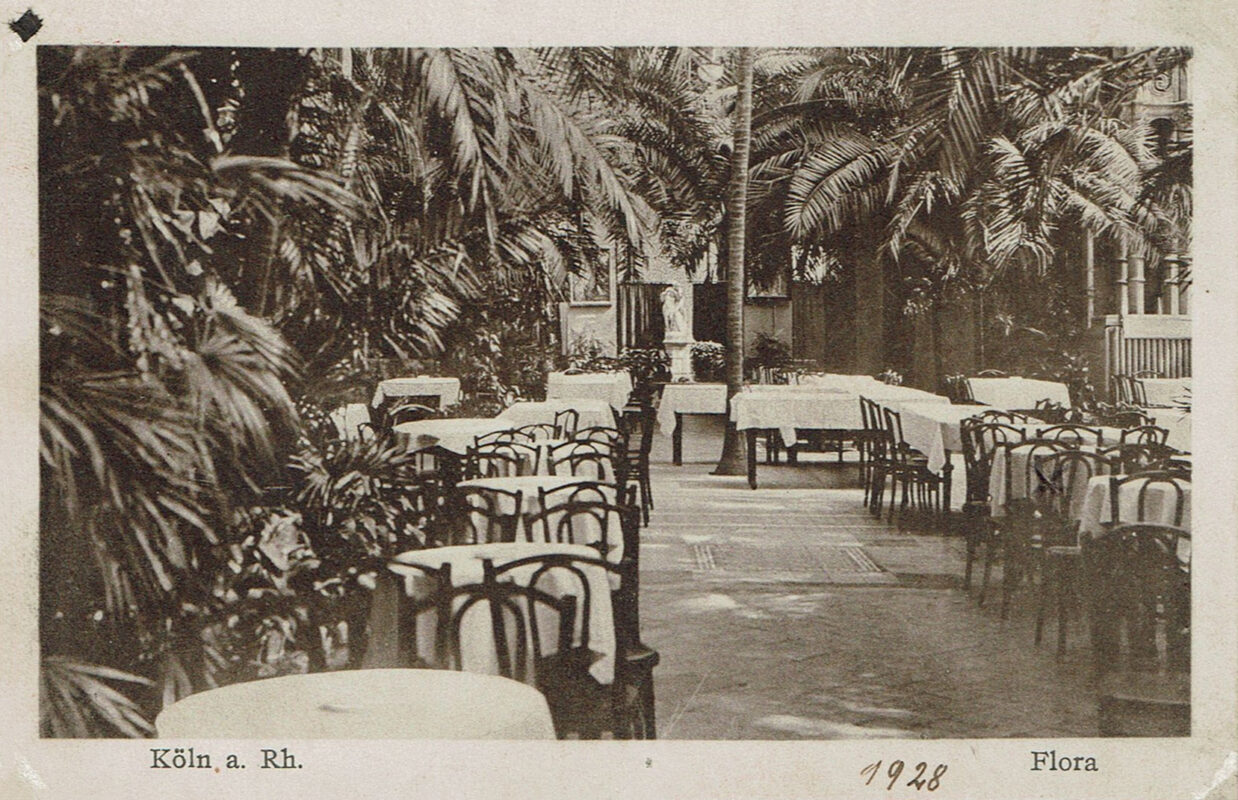

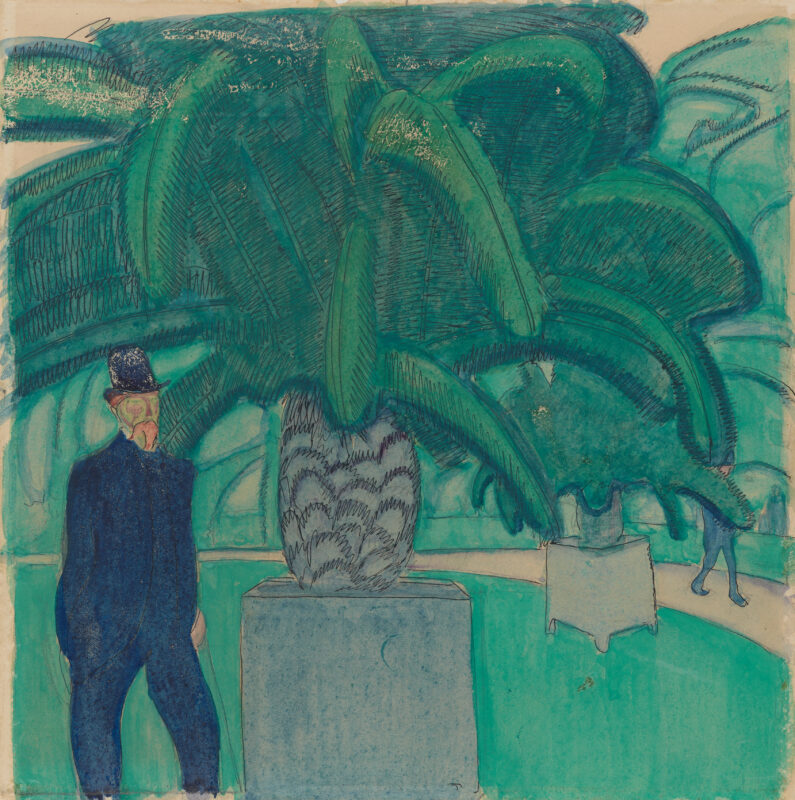

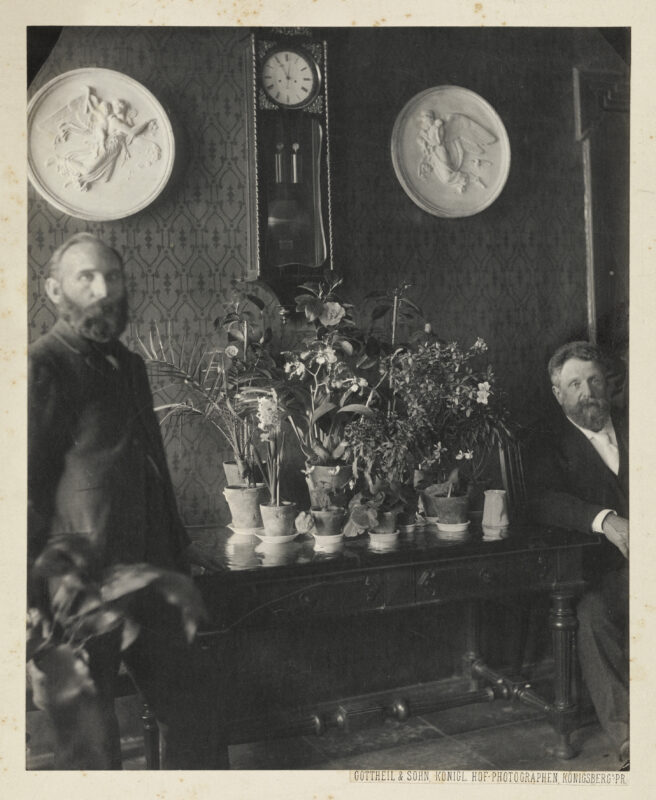

Images of plants are more than just images of plants. Plants always reveal something about people, their desires and fears, and their attitudes toward life and world orders. This applies today as much as it did a century ago, when the artists of urban and technophile modernism took a fresh look at plants. What remains from this period are drawings of tropical indoor gardens, cacti captured on canvas, floral dresses in silver gelatin prints, and buds and sprays rendered in marble and bronze. To bring structure to this mass of images, this exhibition is divided into several chapters that propose various answers to the question: What do pictures tell us about the relationship between humans and plants? This relationship is particularly topical today due to the environmental crisis and the mass extinction of species.

The Plant as the “Other”

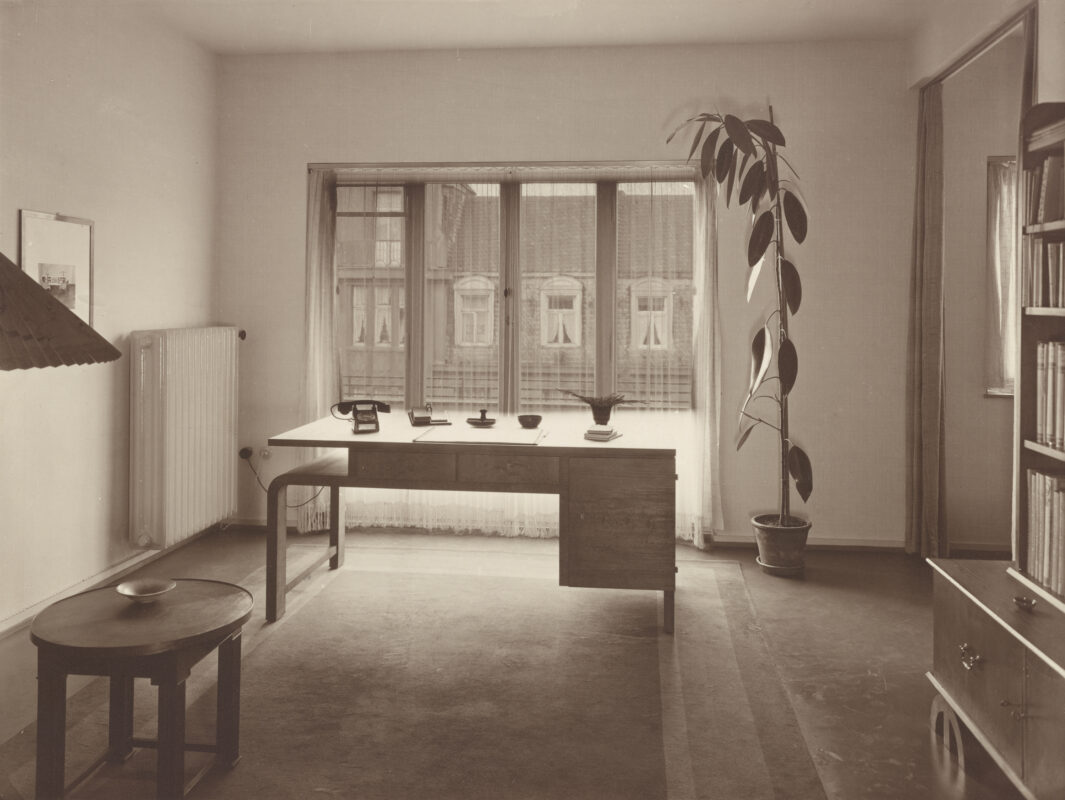

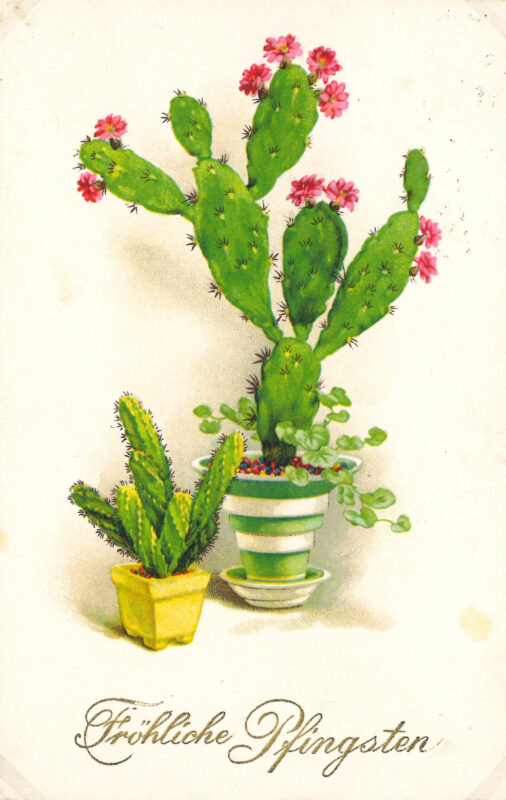

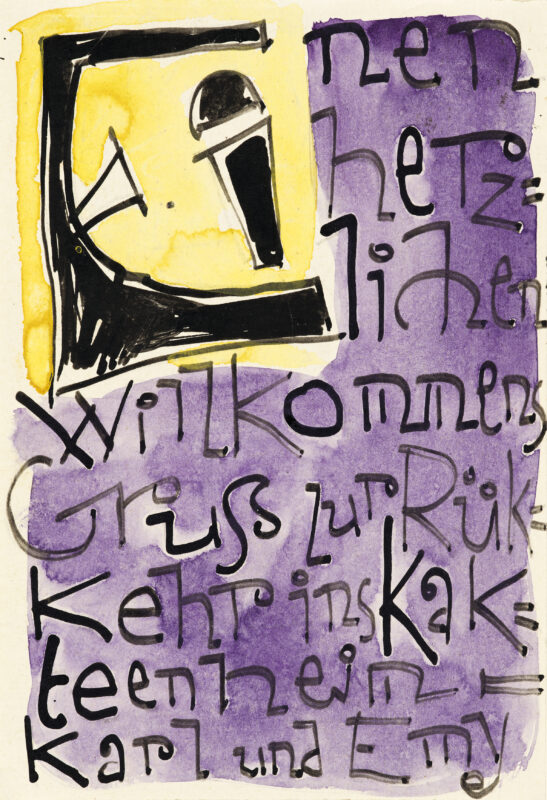

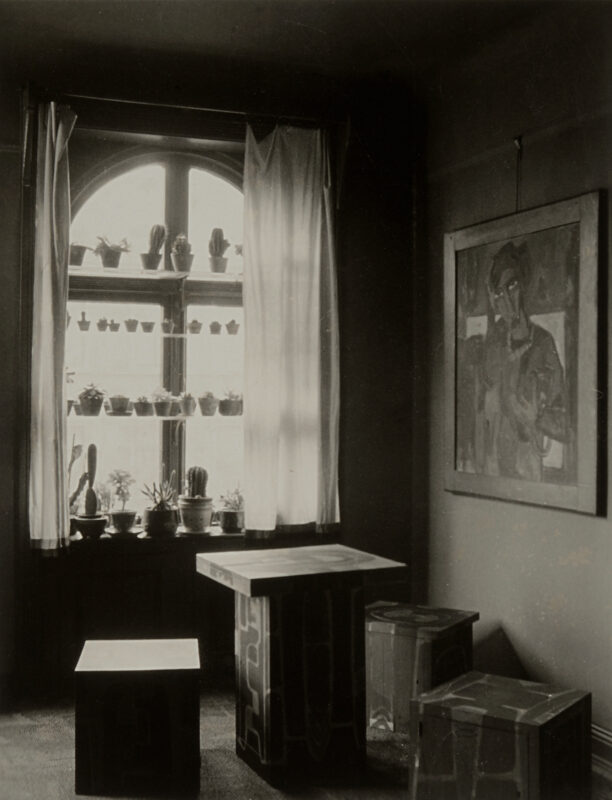

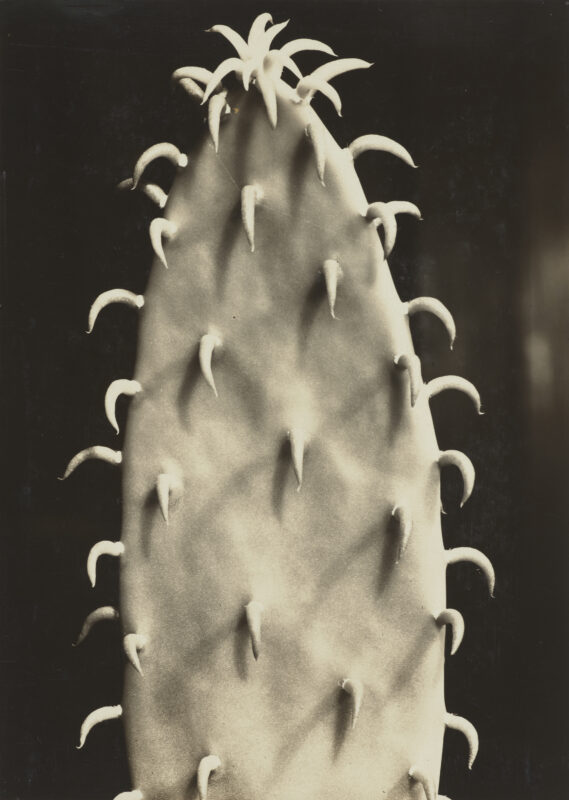

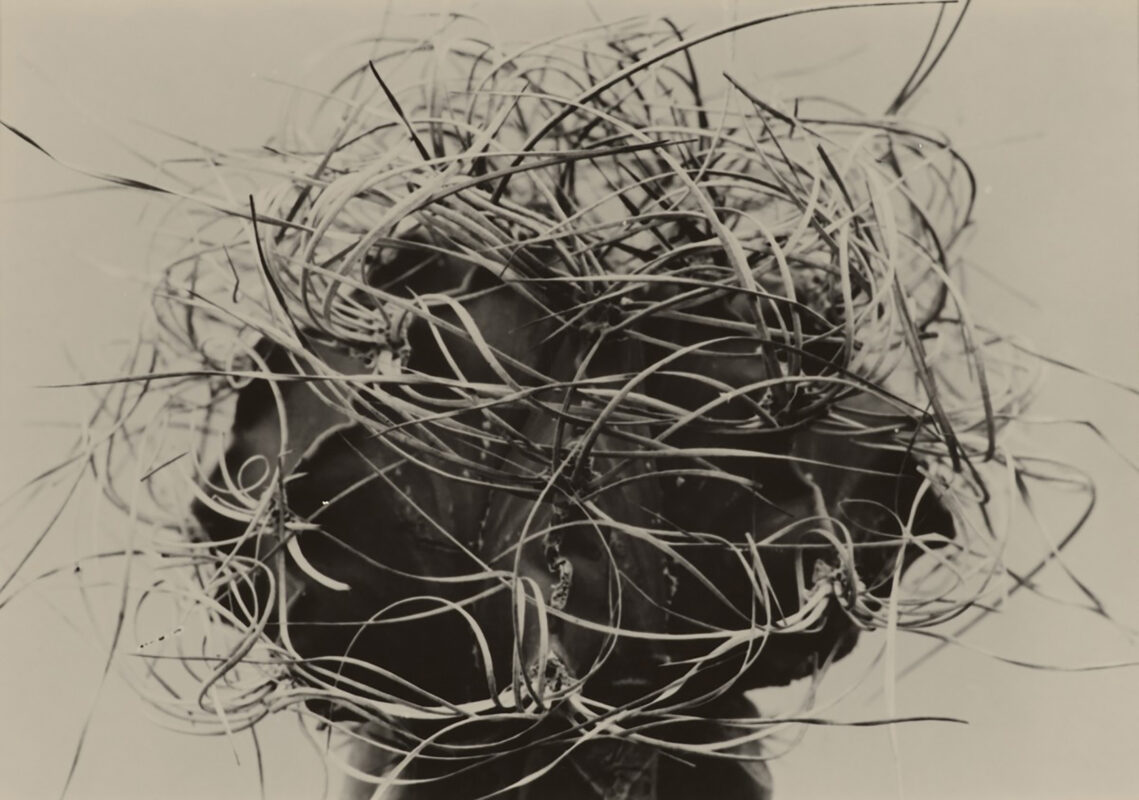

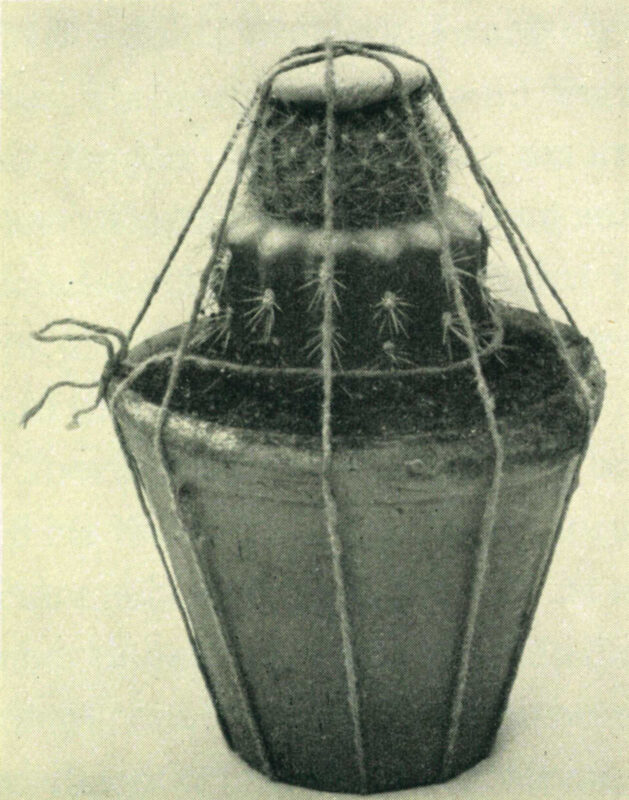

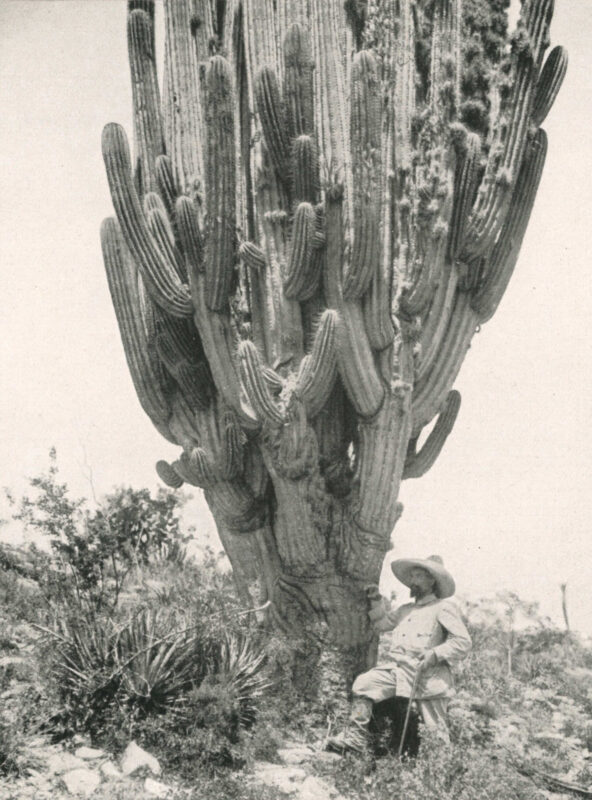

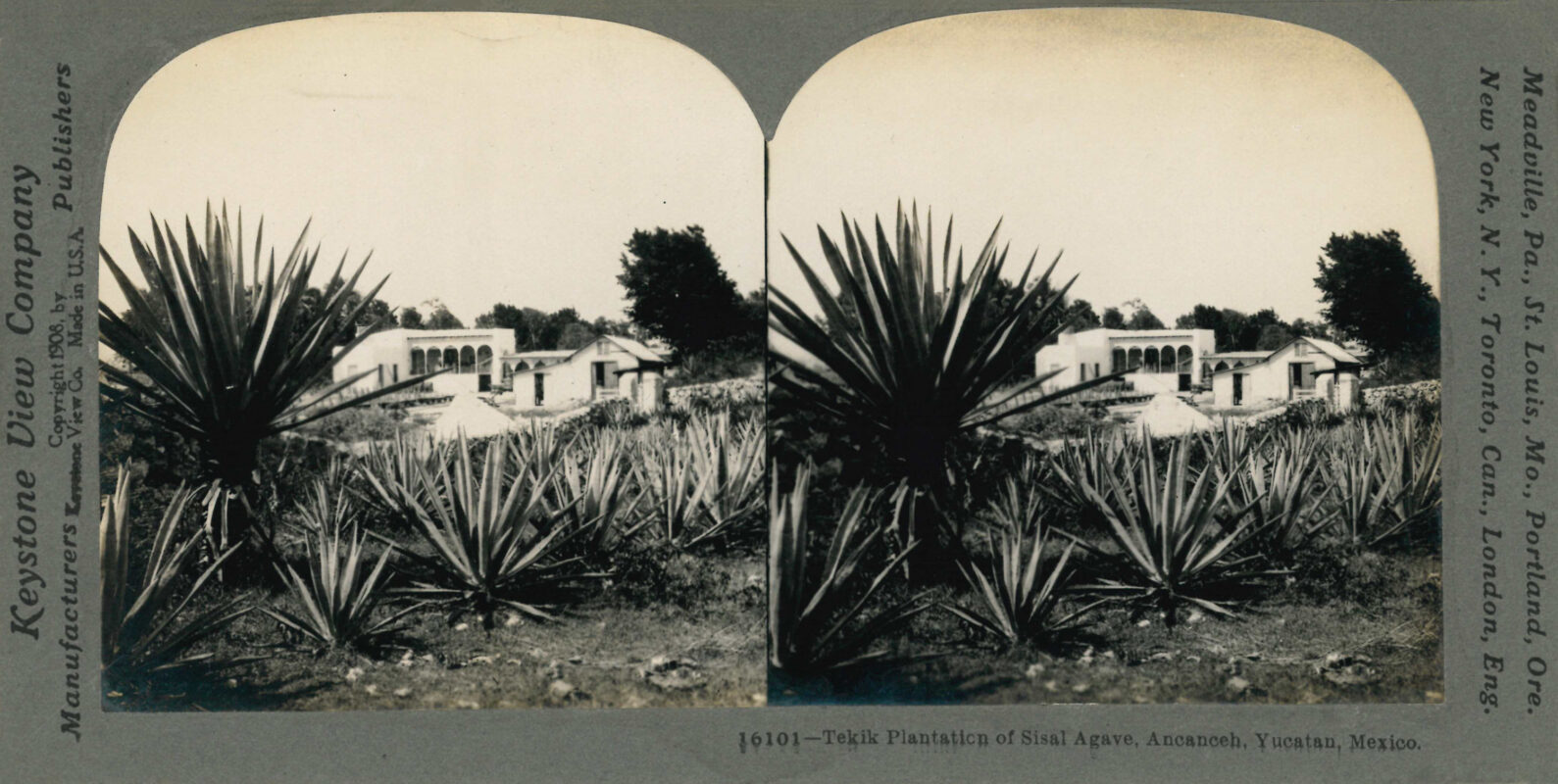

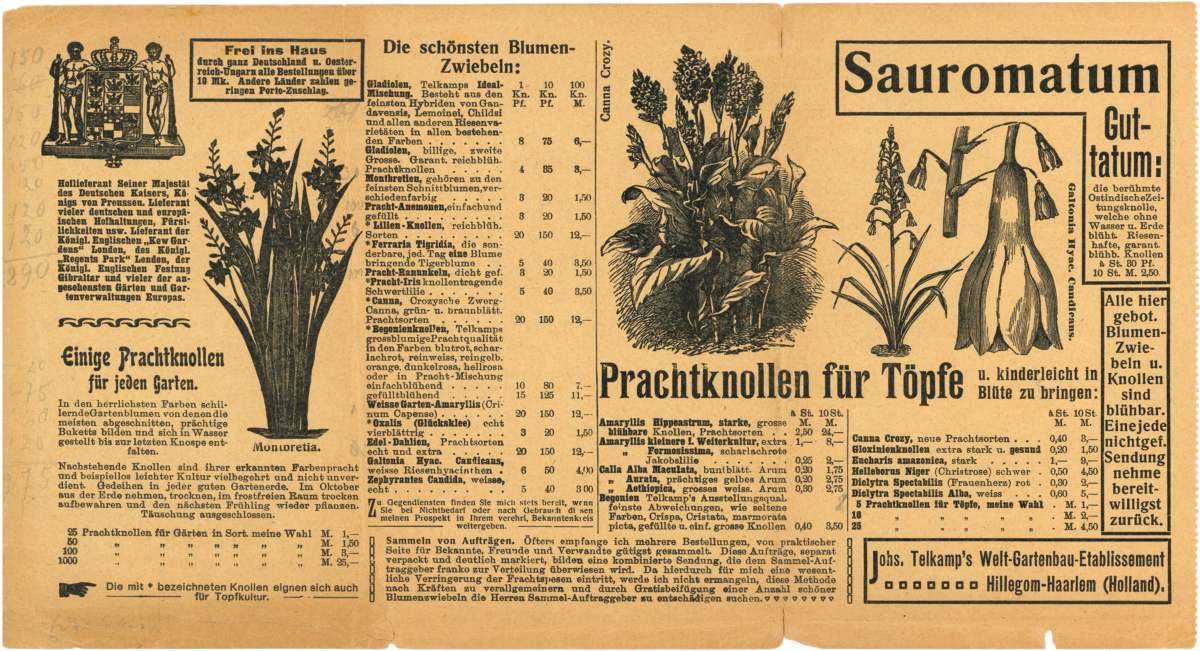

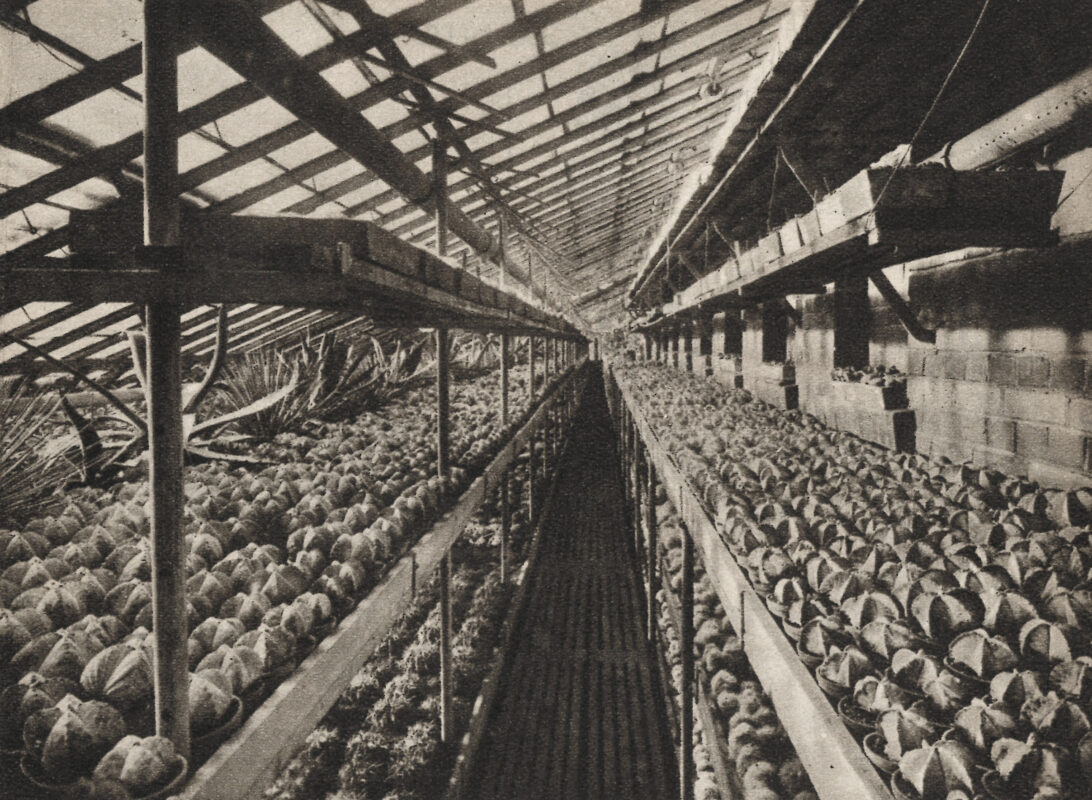

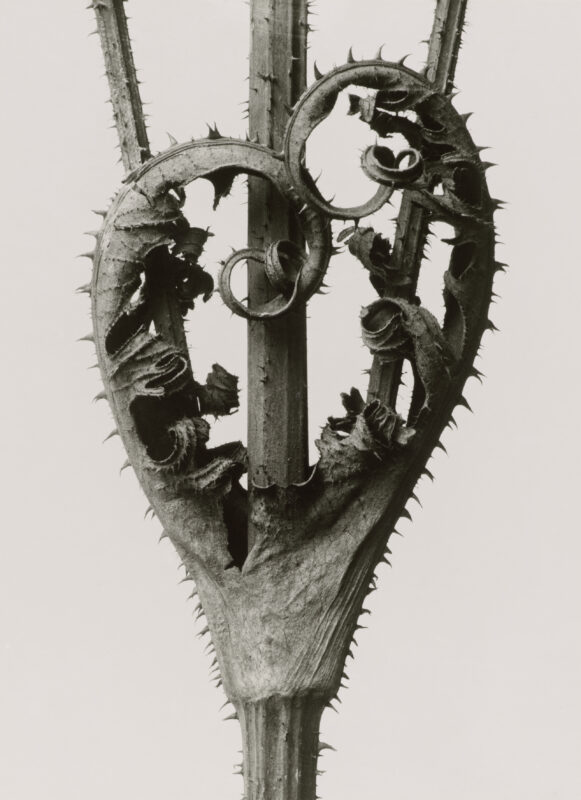

The song “My Little Green Cactus,” by the Comedian Harmonists, extolled a plant that was extremely popular in the early twentieth century. The cactus was considered a “symbol of the exotic, the anti-bourgeois, the notion of traveling around the world,” as the 1925 book Die Schönheit unserer Kakteen (The beauty of our cacti) states. Cacti did not become “ours” until “cactus hunters” such as Curt Backeberg began digging them up in North and South America, disregarding their significance for Indigenous populations and the environmental conditions of their habitats. In Germany, they became the aesthetic and botanical “other.” Similar to rubber trees and monsteras, the distinct forms of cacti were valued; German photographer Albert Renger-Patzsch even called them “natural sculpture.” Meanwhile, the Botanical Central Department for the German Colonies in Berlin was researching how the plantation economy could be intensified with certain food crops. However, this background information remains “out of focus and abstract,” which is how Renger-Patzsch recommended photographing a cactus.

The Appropriated Plant

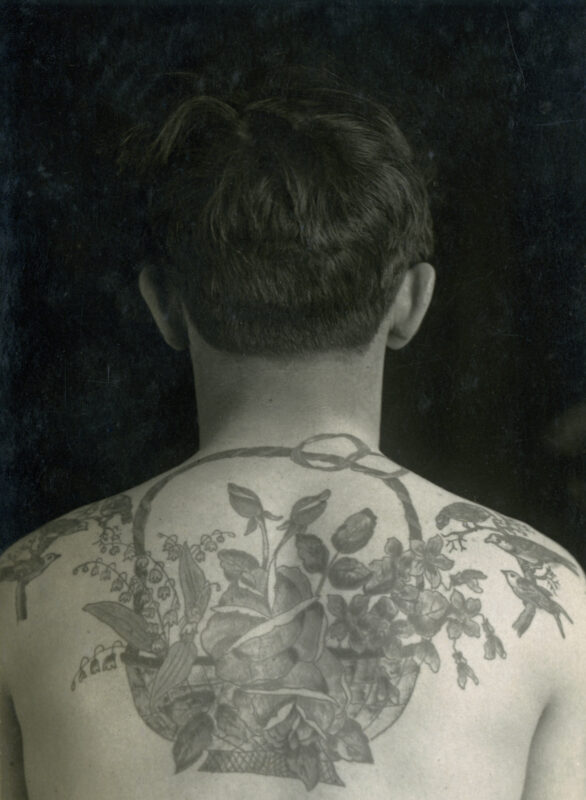

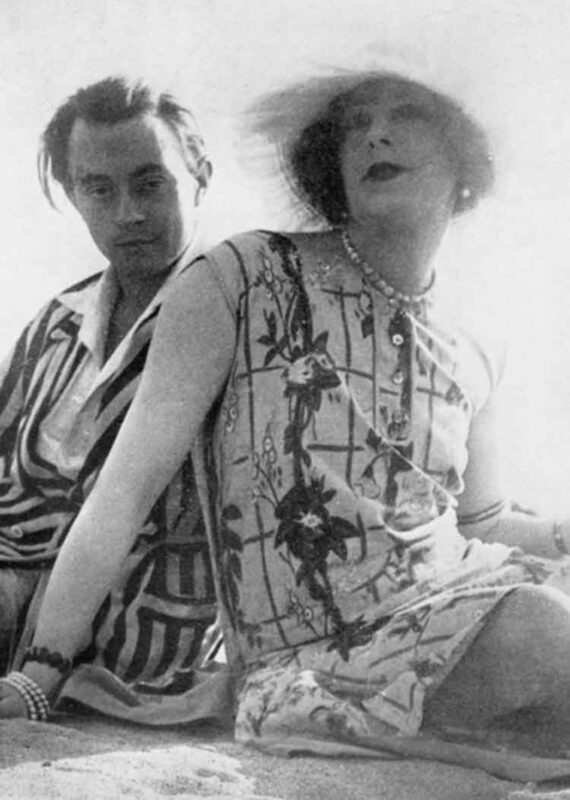

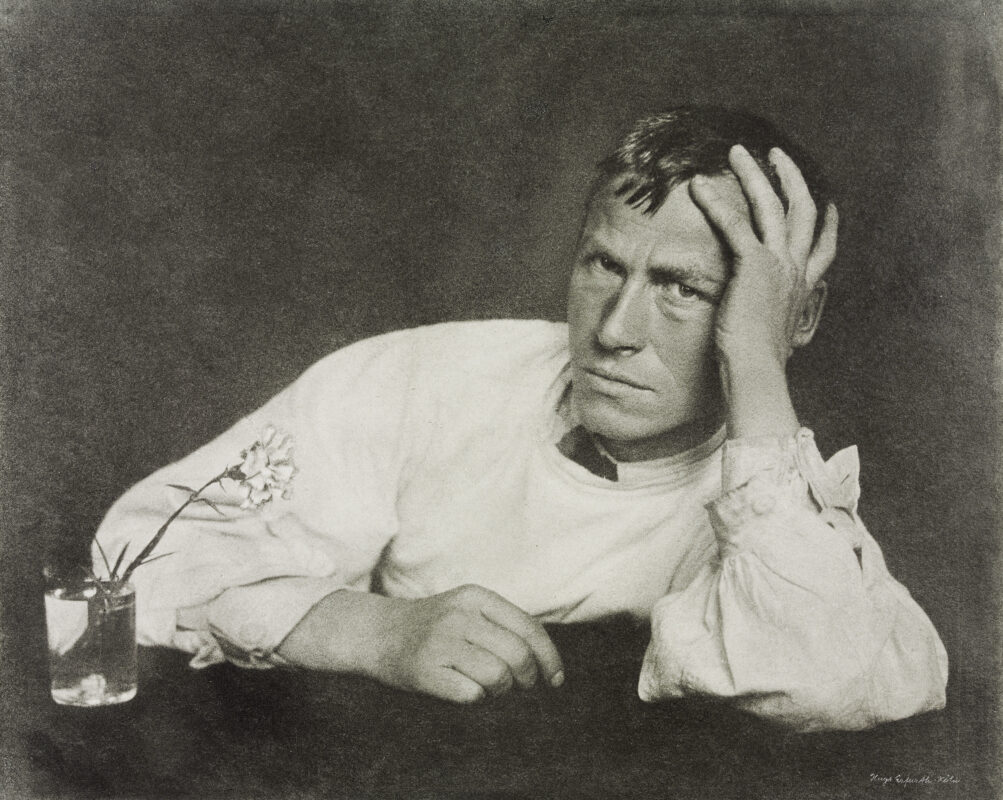

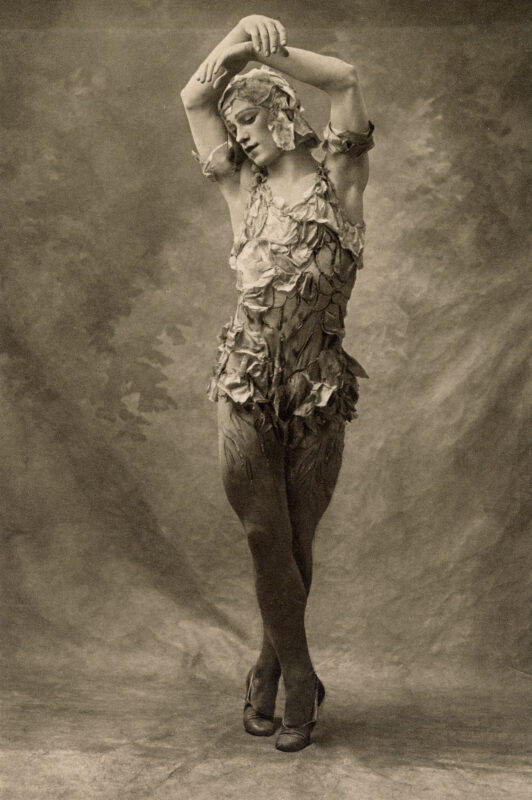

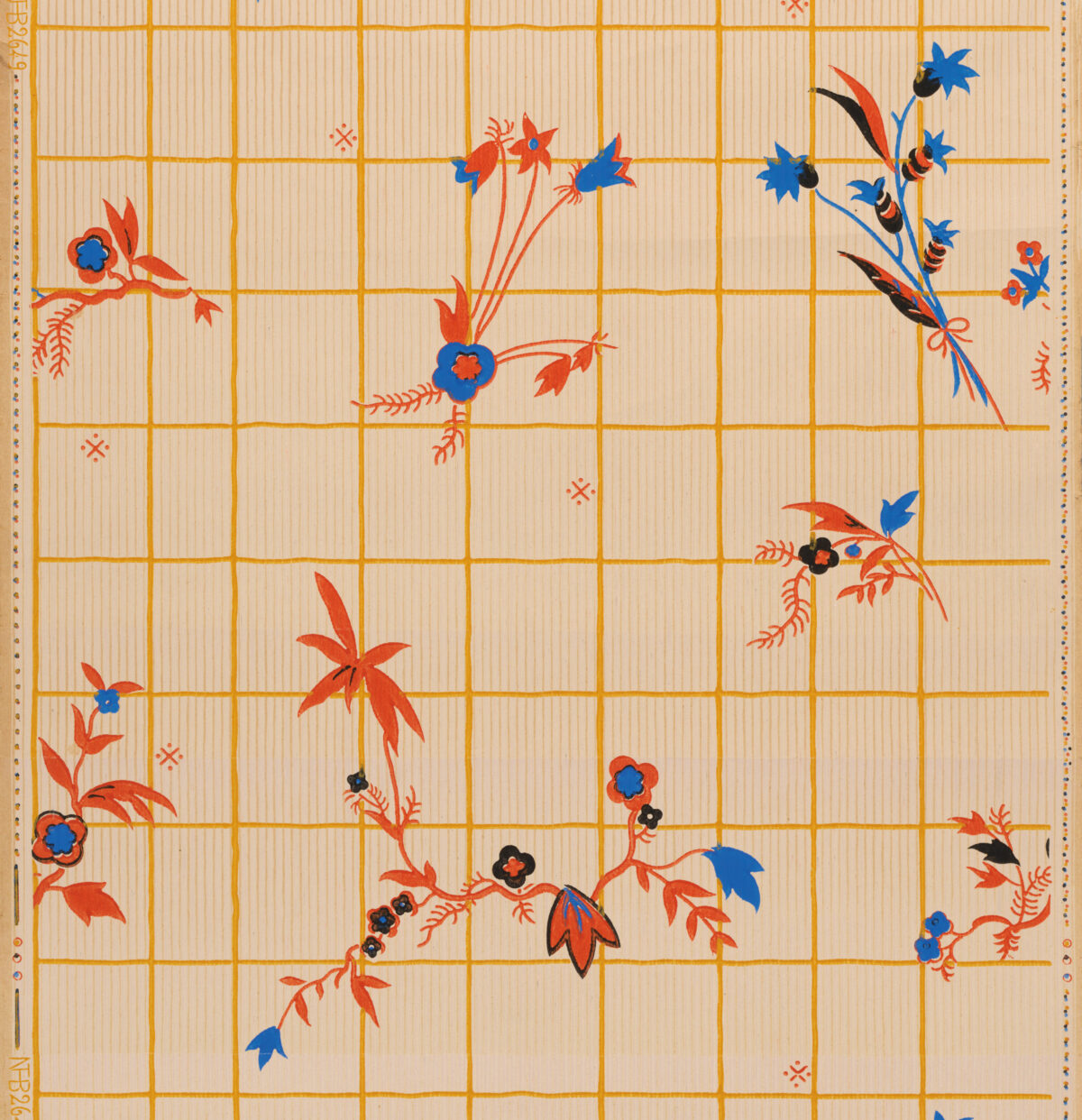

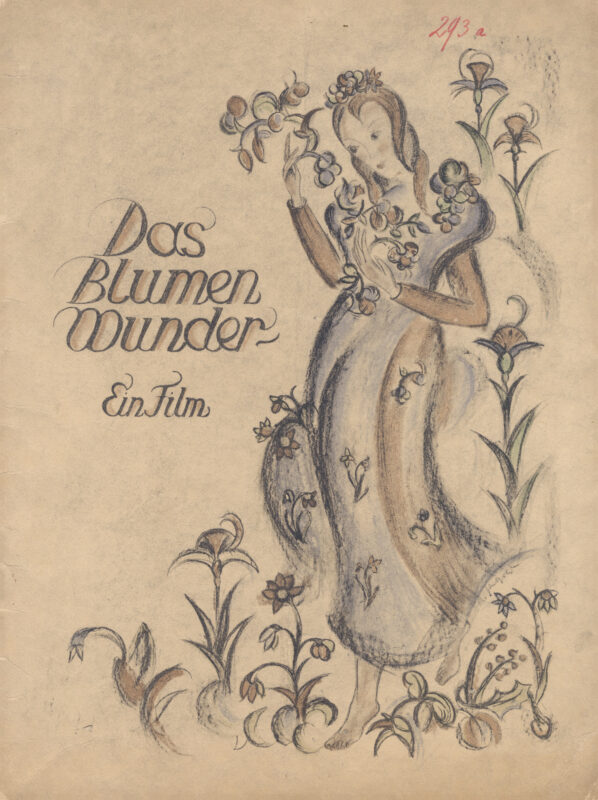

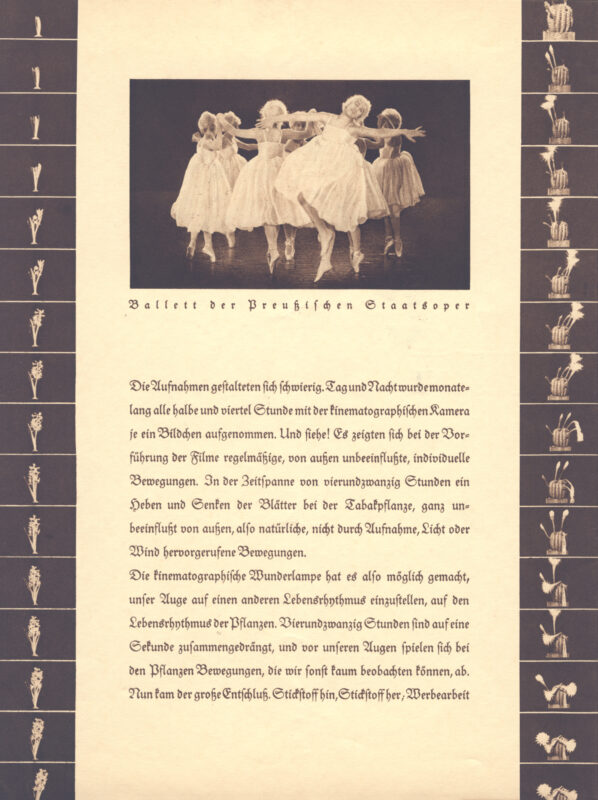

Martha Dix, Anneli Strohal, and Greta Garbo all appear in portraits wearing dresses with floral motifs. Flora, the goddess of flowers in antiquity, lived on in the “New Woman,” who wore her hair short, causing many contemporaries to fear that society was being “masculinized.” Marlene Dietrich met this unease with an oversized flower on the lapel of her tuxedo and an ironic smile. The painter Lili Elbe, who in the 1930s was one of the first people to have gender confirmation surgery, also wore dresses with floral motifs to emphasize her femininity. For millennia, Western concepts of womanhood had been linked to flowers; however, hidden under clothing and less public, people of all genders had flower tattoos. In 1911, dancer Vaslav Nijinsky performed all over the world, including Cologne, in the ballet Le Spectre de la rose, prompting the Berlin newspaper Berliner Tageblatt to describe him as the “epitome of the stimulating and seductive scent of flowers.” In his role as The Rose, wearing a costume covered in pink silk petals, Nijinsky liberated ballet from conventional gender roles.

Blossoms and Gender

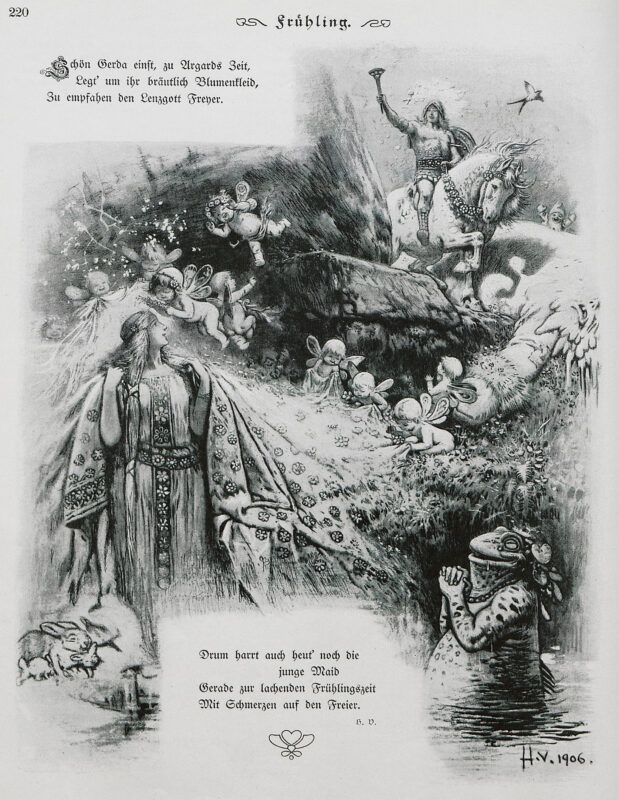

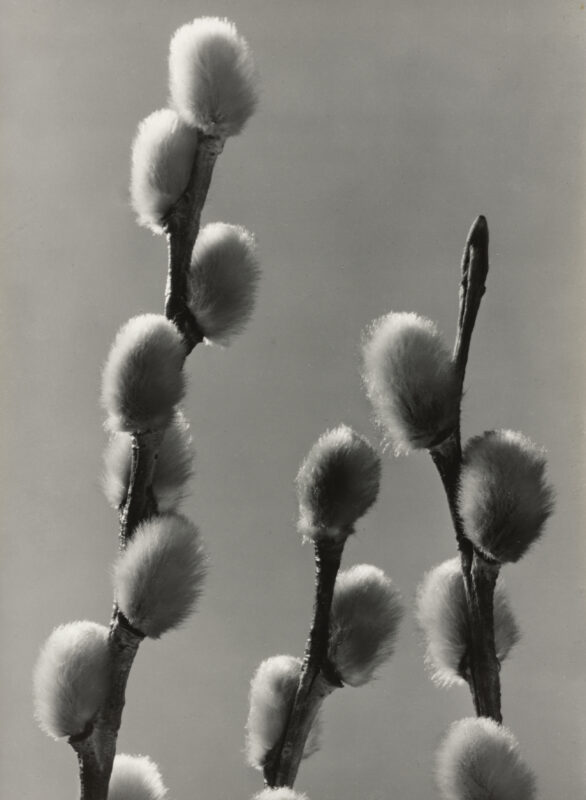

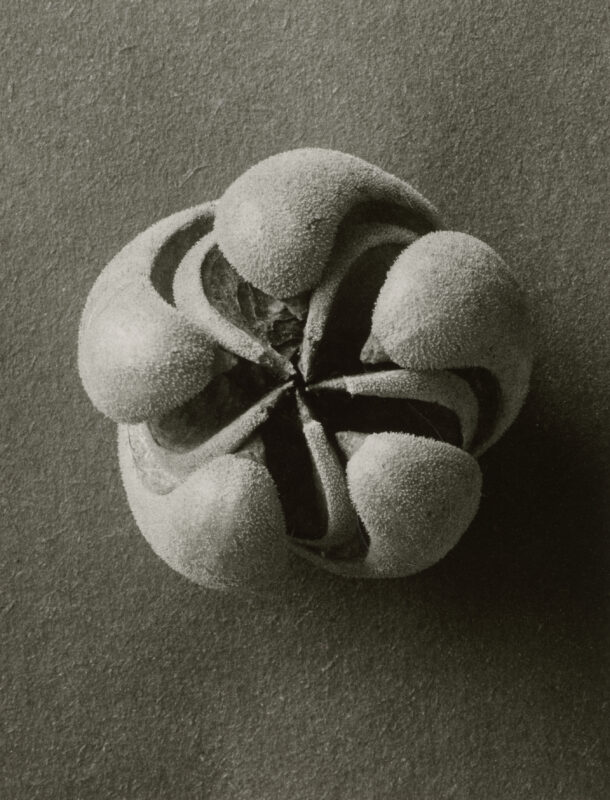

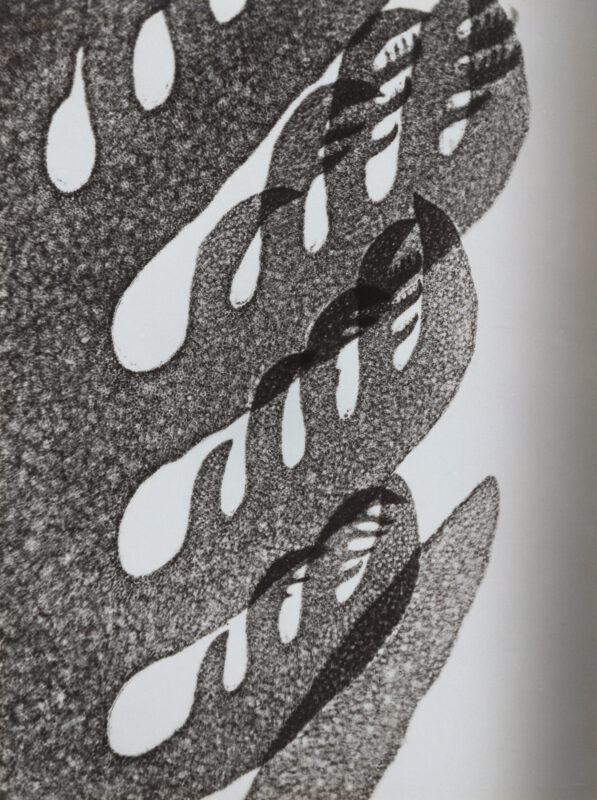

Blossoms are the sexual organs of flowers. Although most flowers are hermaphrodites with stamens and pistils, scientists like the Swedish botanist Carolus Linneaus (1707–1778) described them as distinctly either male or female, transferring them into the heterosexual mental models of humans. Linneaus wrote: “The flowers’ leaves . . . serve as bridal beds which the Creator has so gloriously arranged, adorned with such noble bed curtains, and perfumed with so many soft scents that the bridegroom with his bride might there celebrate their nuptials with so much the greater solemnity.” The sexualization of flowers continued into the twentieth century and can be observed in works such as Hans Arp’s sculpture Garland of Buds.

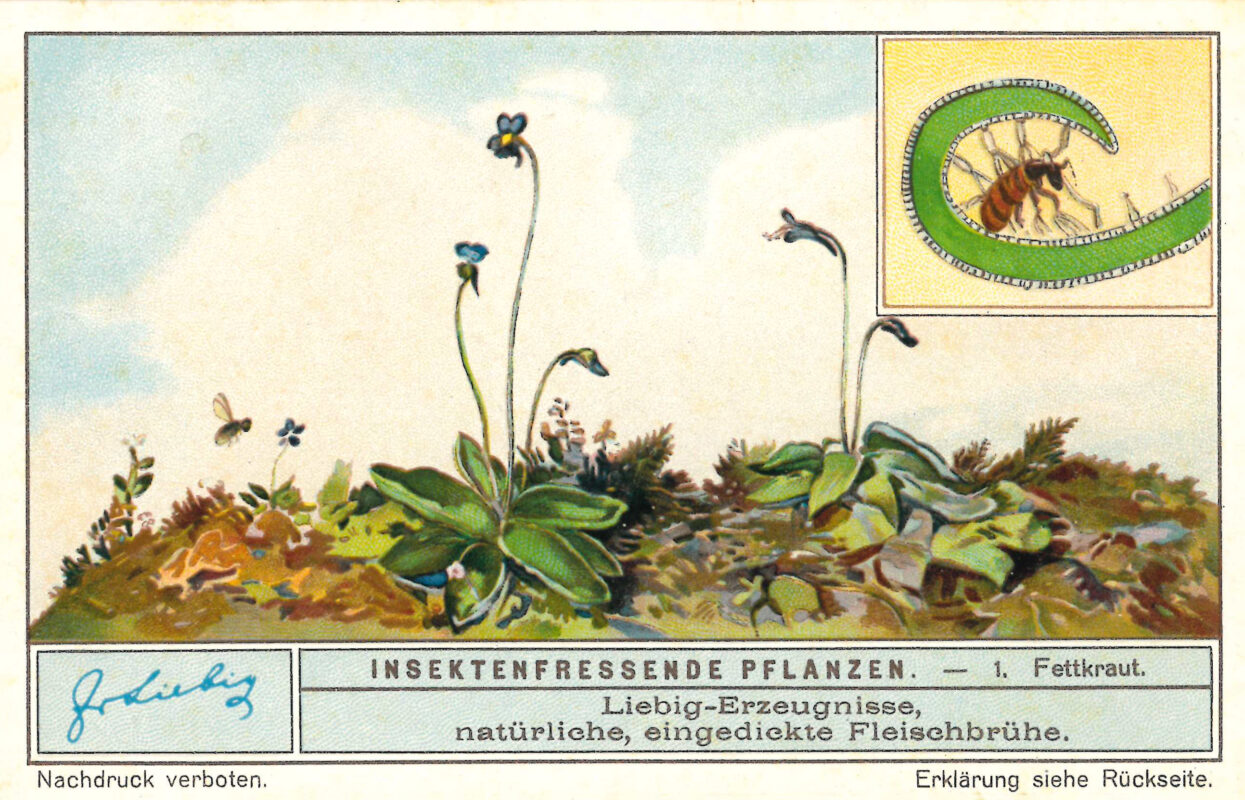

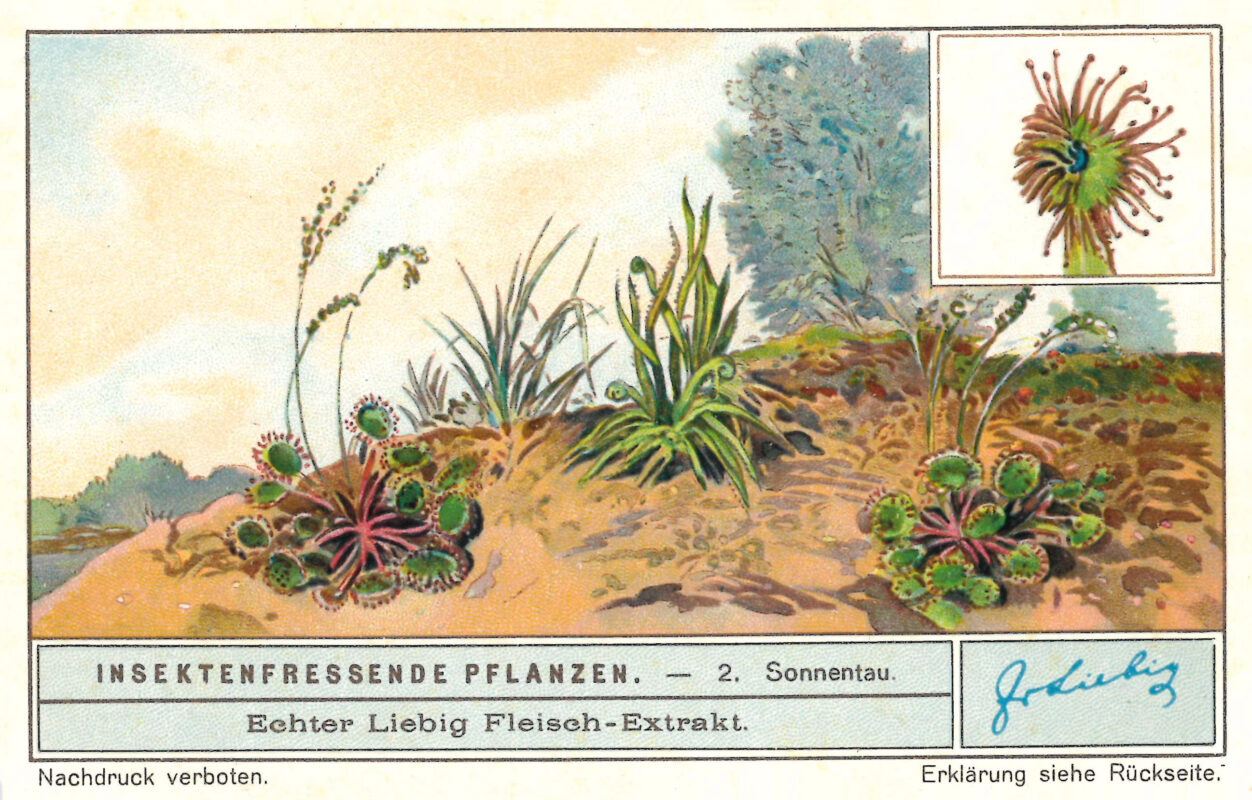

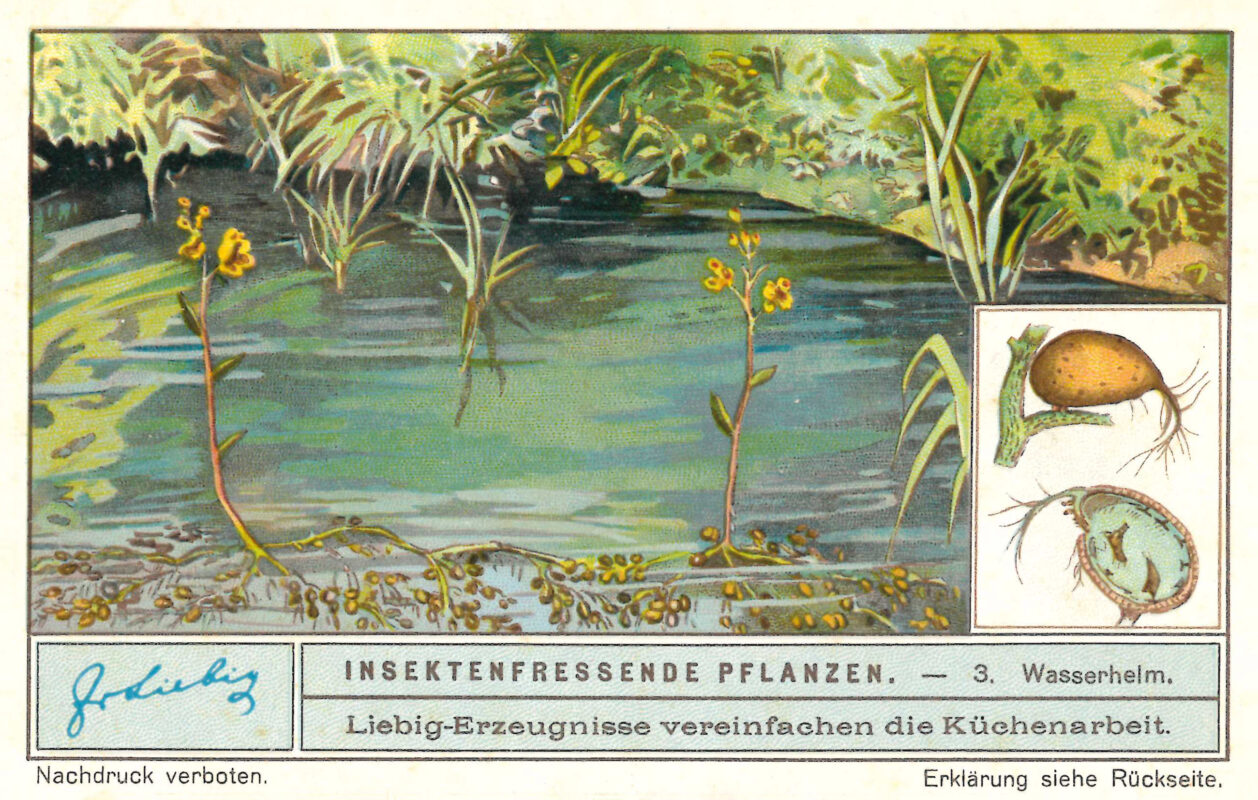

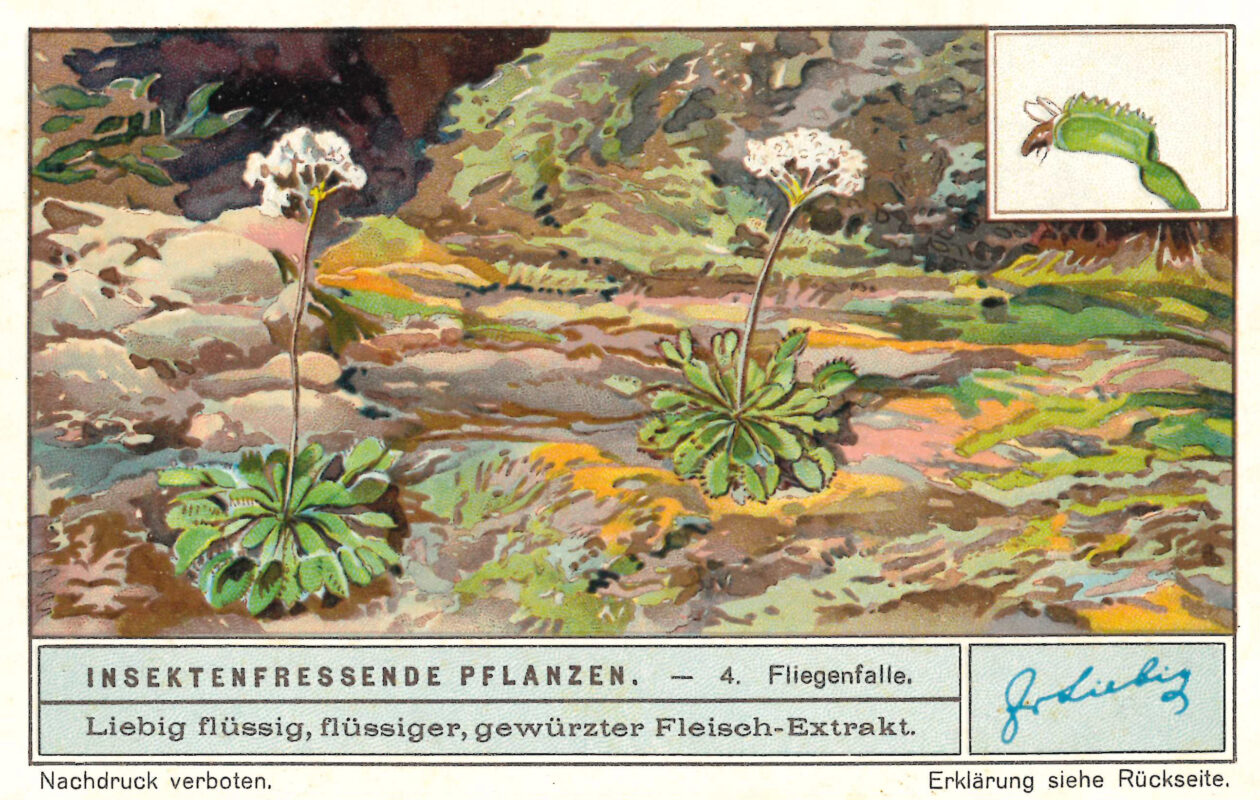

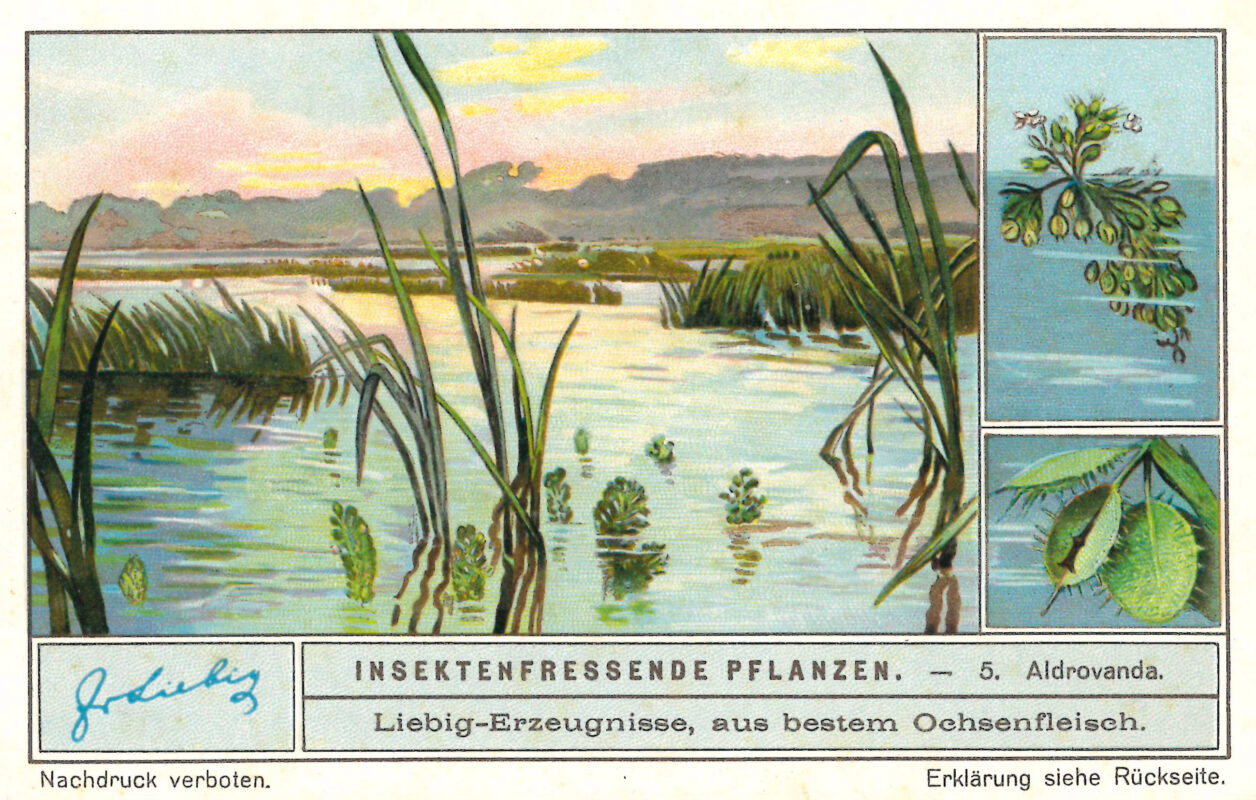

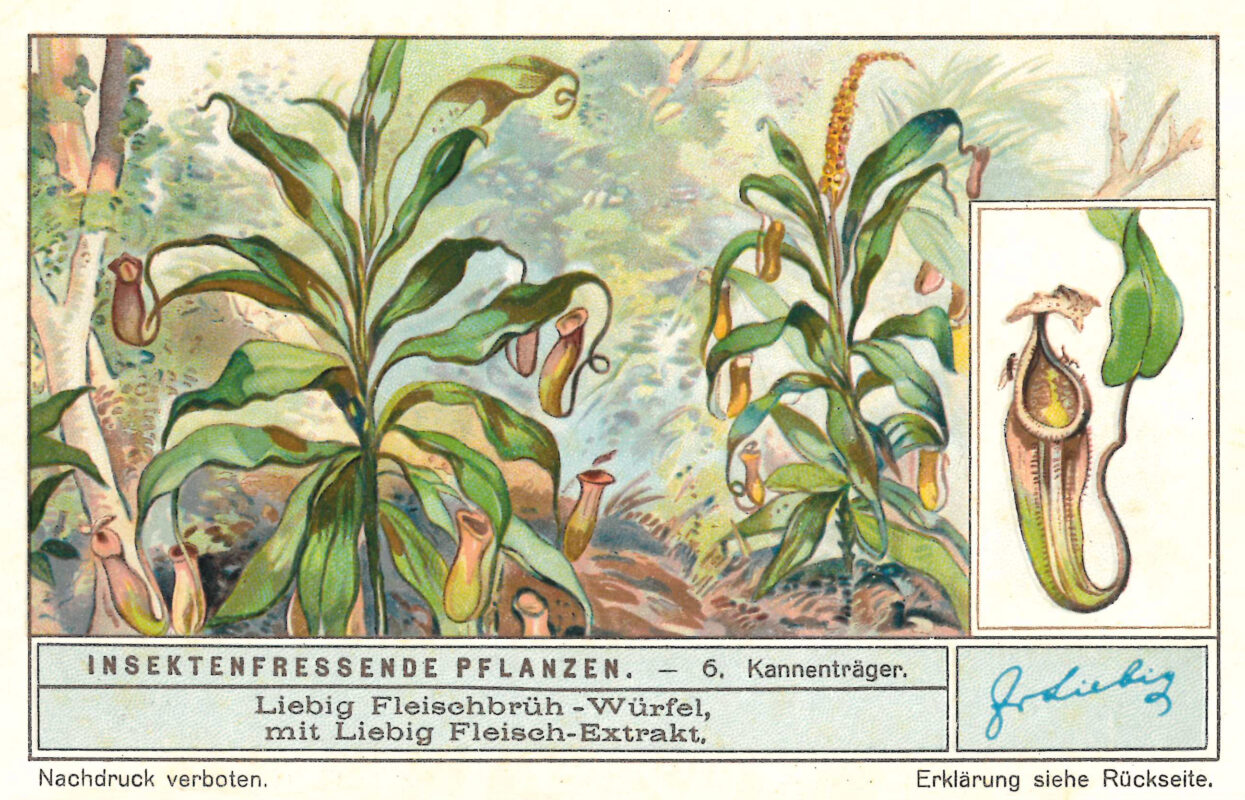

Plant Horror

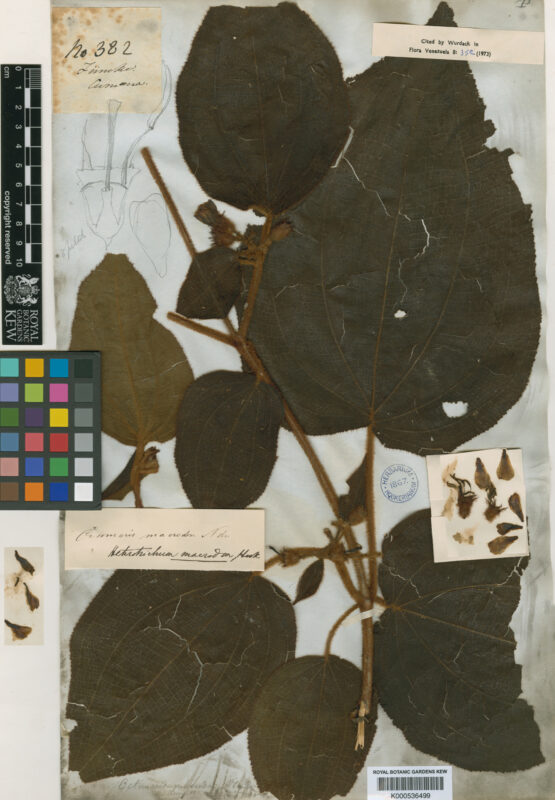

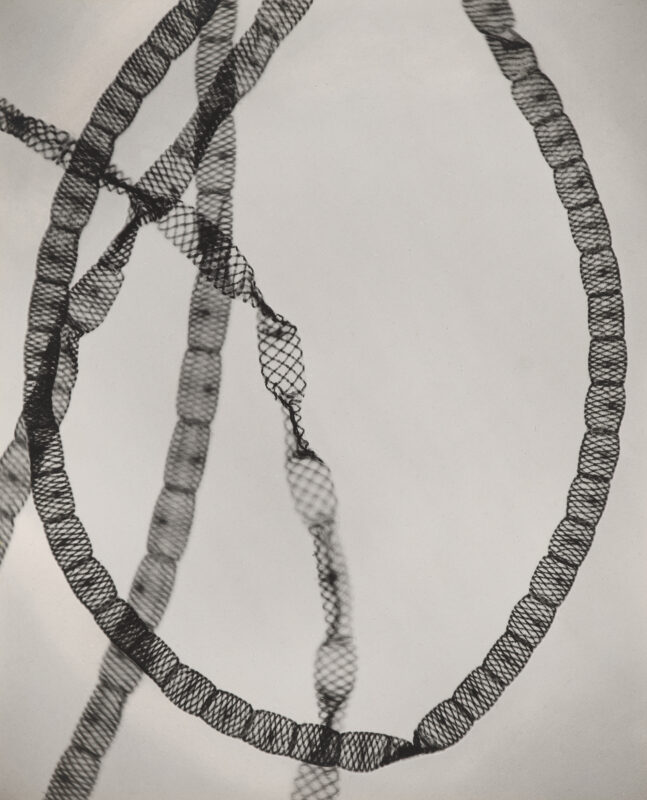

Horror is a fear of phenomena outside the realm of the familiar. A century ago, plants resembling animals or humans were a popular motif of the genre, and this holds true today. Writing about the book Alraune (Mandrake, 1911) by Hanns Heinz Ewers, the artist George Grosz commented that it is “currently the book of the season . . . the most read in the lending libraries.” The book, which was turned into a film in 1928, tells the story of a femme fatale named after the poisonous mandrake root. Meanwhile, in the film Nosferatu (1922), footage of a Venus flytrap was used to compare the carnivorous plant to a vampire—after all, an animal eating plant was considered the reversal of a supposedly natural order. Finally, in Gustav Meyrink’s 1913 story Die Pflanzen des Dr. Cinderella (The plants of Dr. Cinderella), it was an “animalistic” creeping vine that terrified readers:

“I was chilled by horror, and I made my way along the curve of the corridor. Once, I touched the wall and grasped a splintery wooden lattice of the sort that is used for climbing plants. There seemed to be great numbers of them growing on it, for I almost got caught in a network of stem-like vines. The incomprehensible thing was, however, that these plants, or whatever they were, seemed to be full of warm blood and felt generally quite animalistic to the touch. . . . In this instant, a light flickered somewhere and illuminated the wall in front of me for a second. What I had ever experienced in terms of fear and terror was nothing in comparison to what I felt now. . . . They all seemed to be parts taken from living bodies, assembled with incredible art, robbed of their human animation, and brought down to a purely vegetal growth.”

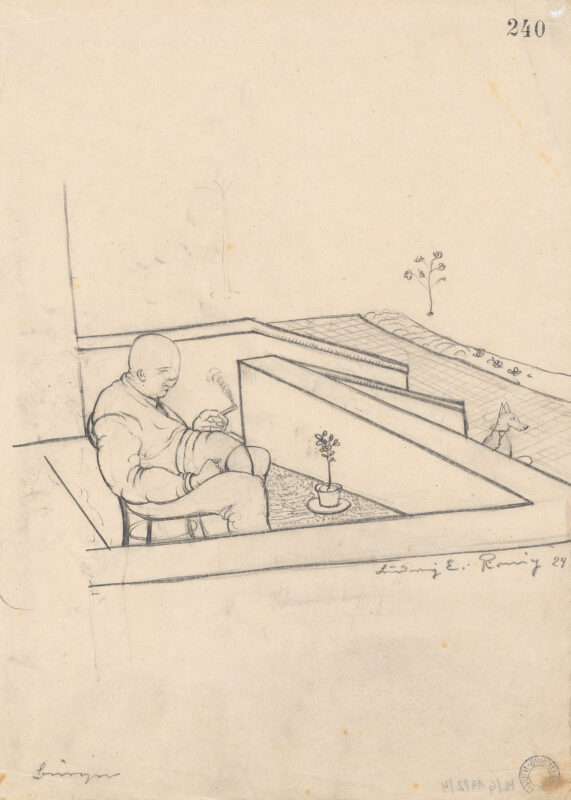

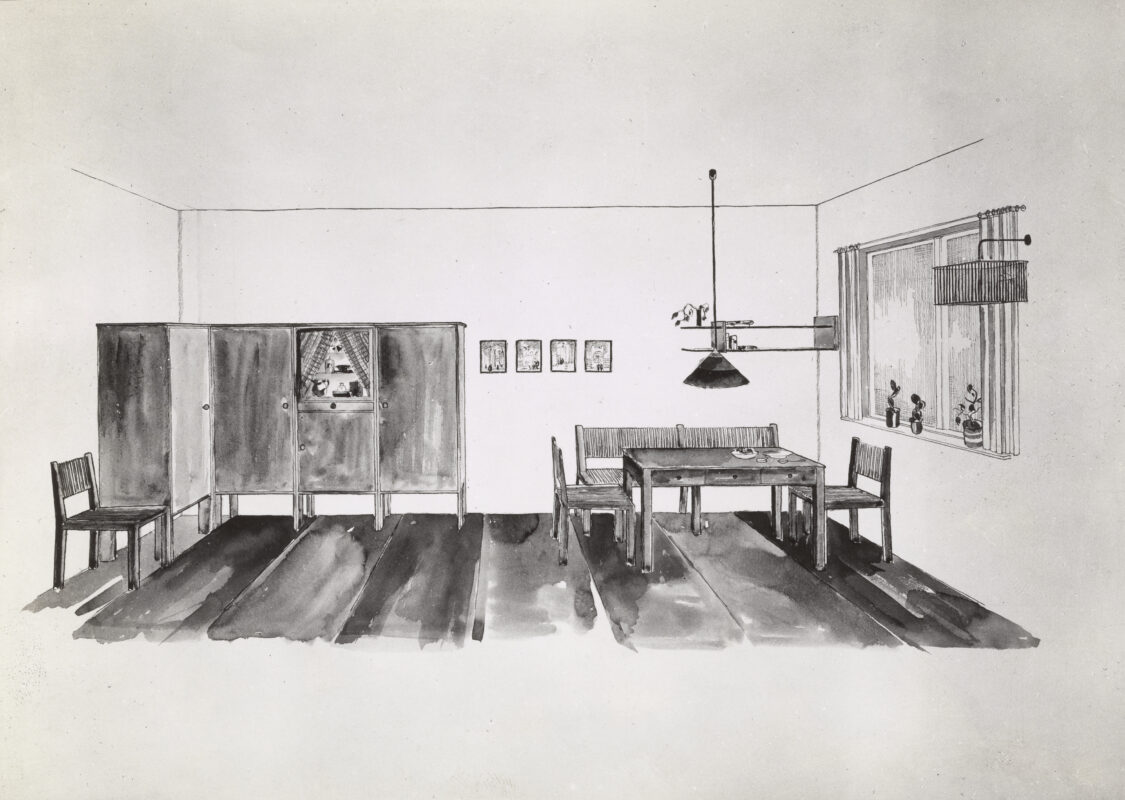

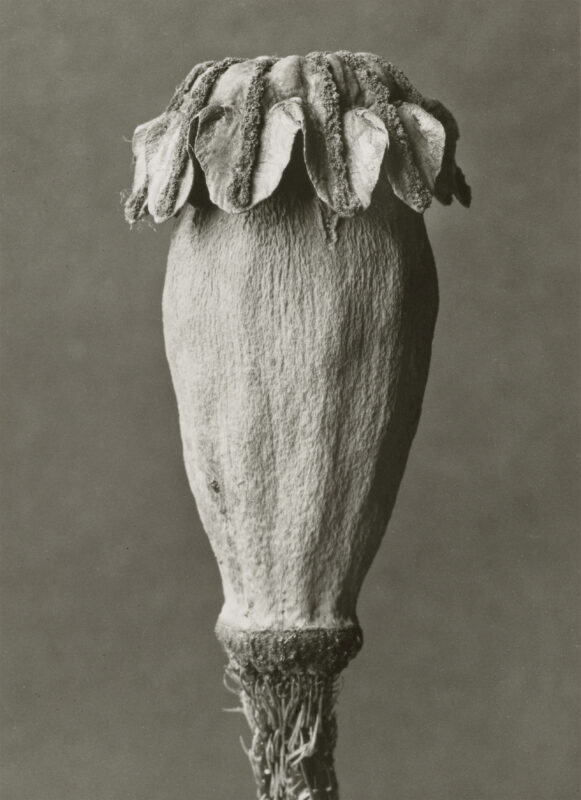

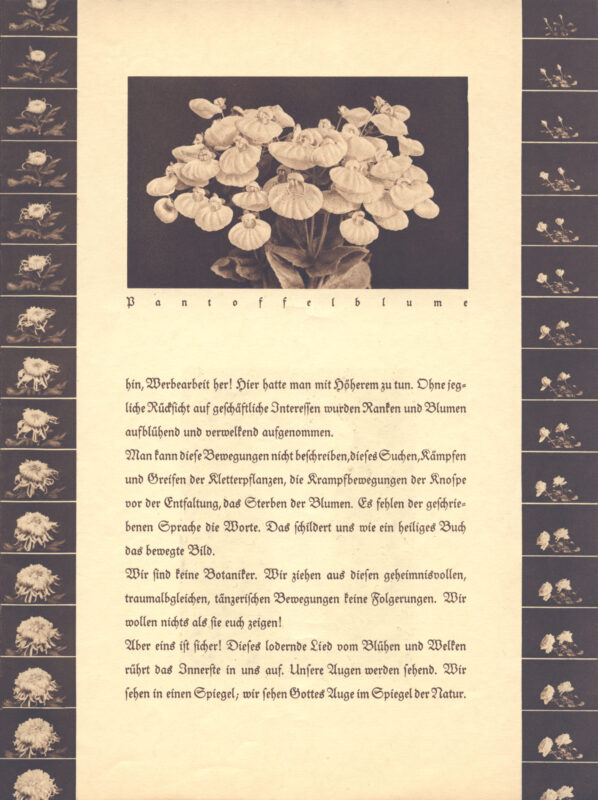

The Plant as Form and Color

The photographer Karl Blossfeldt was not interested in the names and functions of plants. What intrigued him was their form, which he revealed by pruning the plants he photographed—often to the point of nonrecognition so they could be used by artisans as reference material for their designs. Plants even served as “building material” for professional florists, as the German art historian Alfred Lichtwark reported in 1905: “There has been a considerable development in the art of arranging flowers in the last few years. Since green leaves were considered raw, arrangers looked for brown and yellow ones, and if a flower only had green leaves, the fault was corrected by combining it with the brown leaves of another. For years in Berlin, I only saw roses with yellow or brown mahonia leaves, never with their own leaves, and it was difficult for anyone standing in front of a Berlin flower shop to convince themselves that the ‘arrangements’ lying there on the black velvet were really produced with living flowers and not artificial ones.” Others, such as the artist Karl Schmidt-Rottluff, used flowers, including the poisonous larkspur, to add an accent of color to a painting.

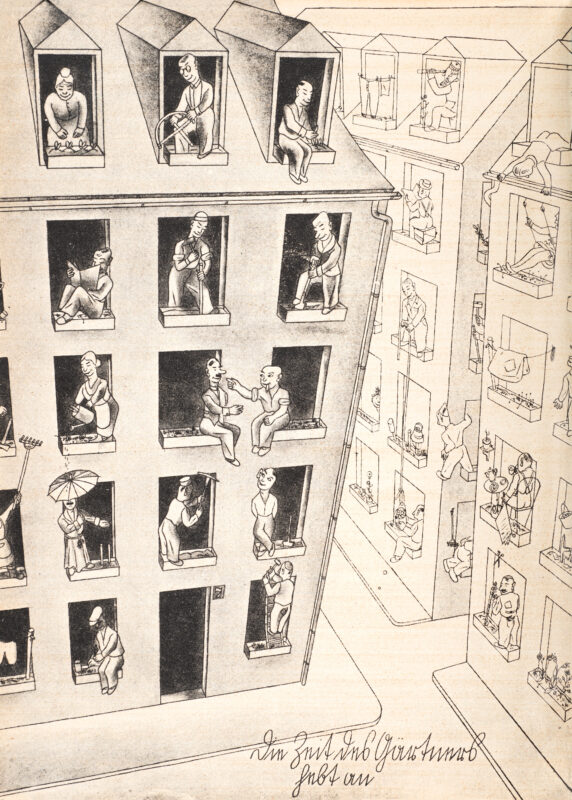

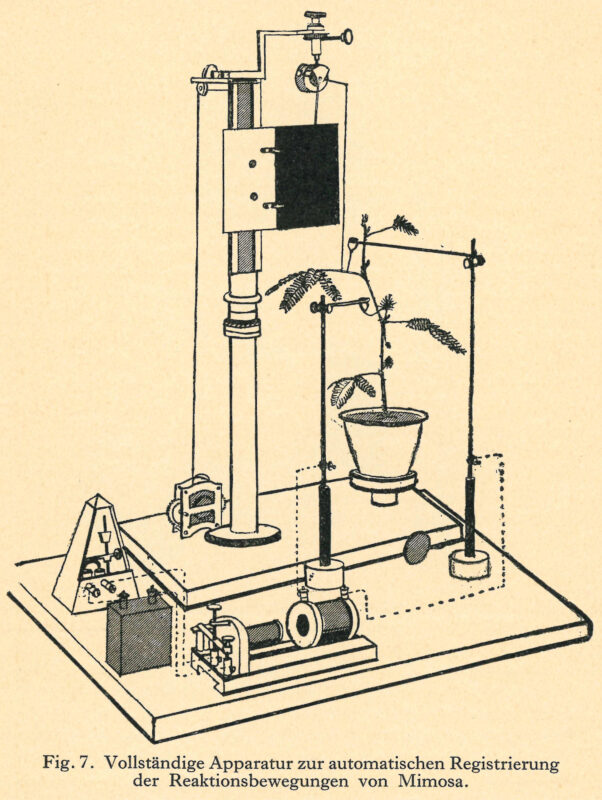

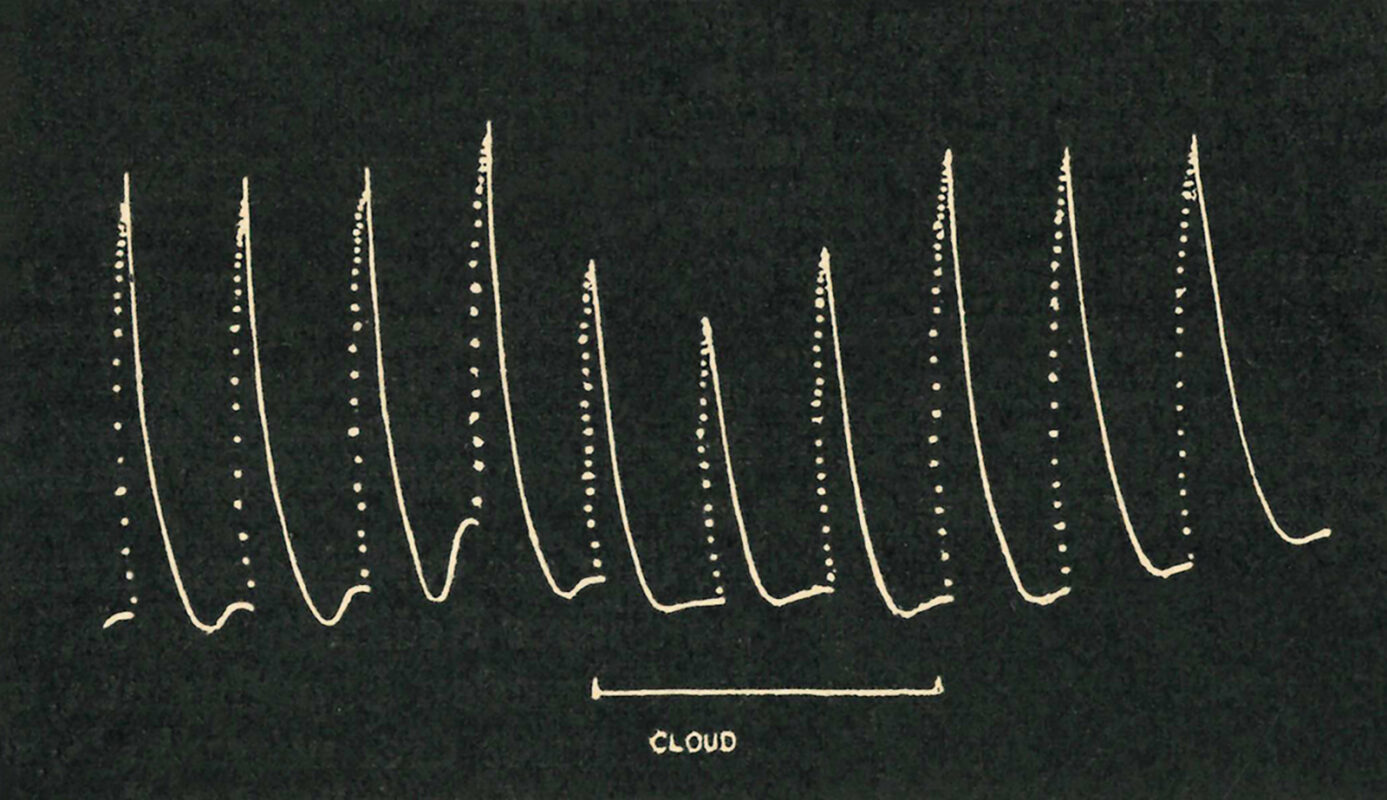

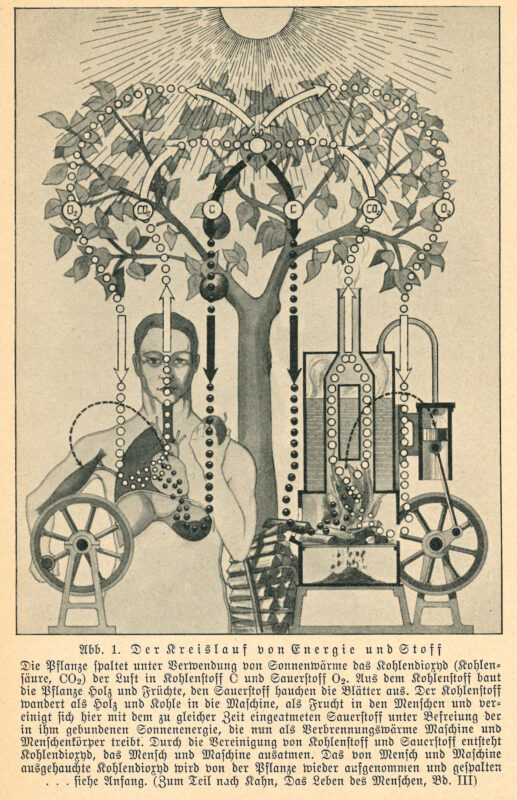

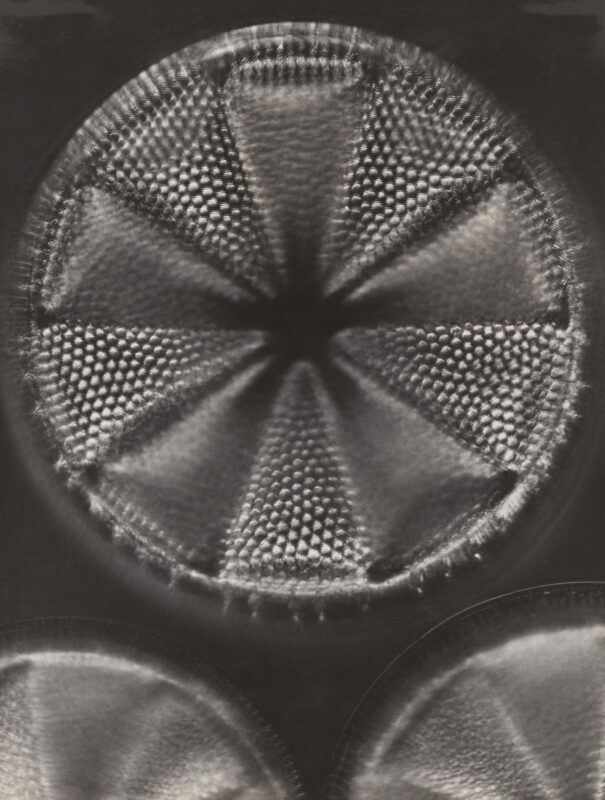

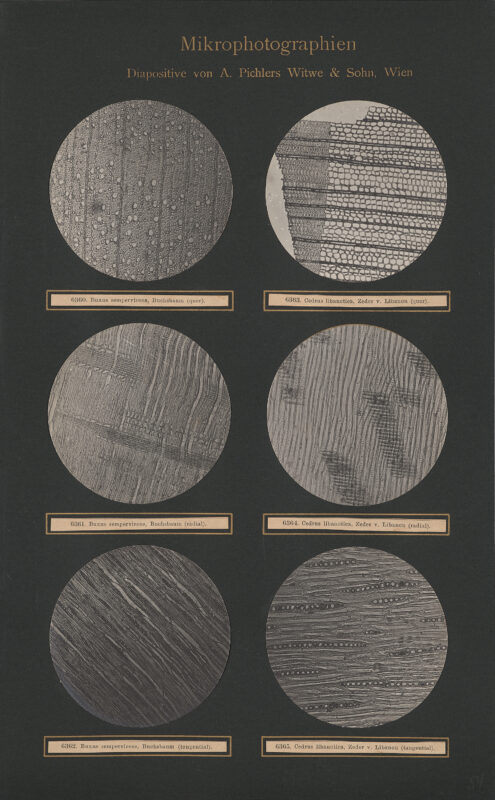

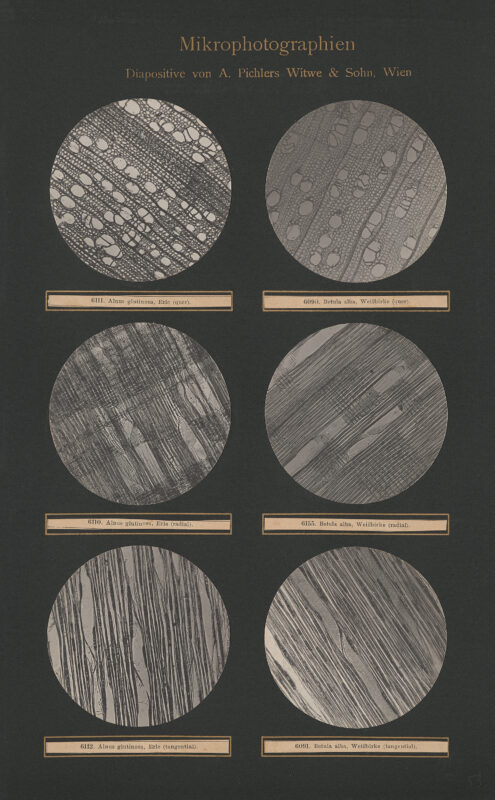

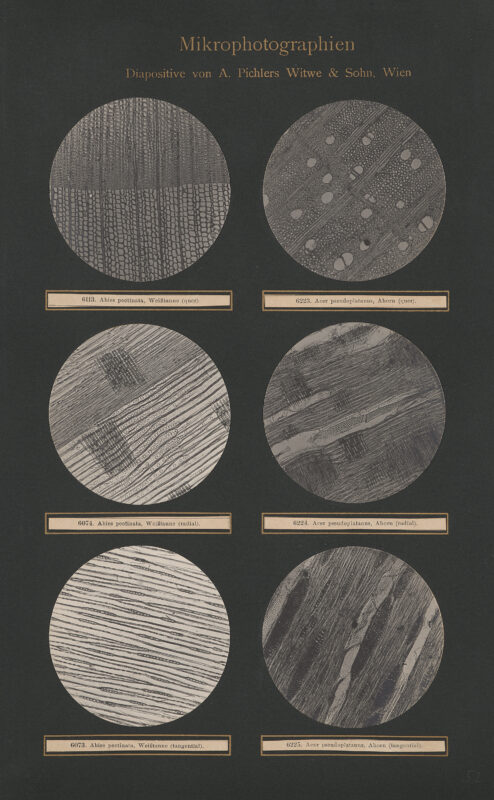

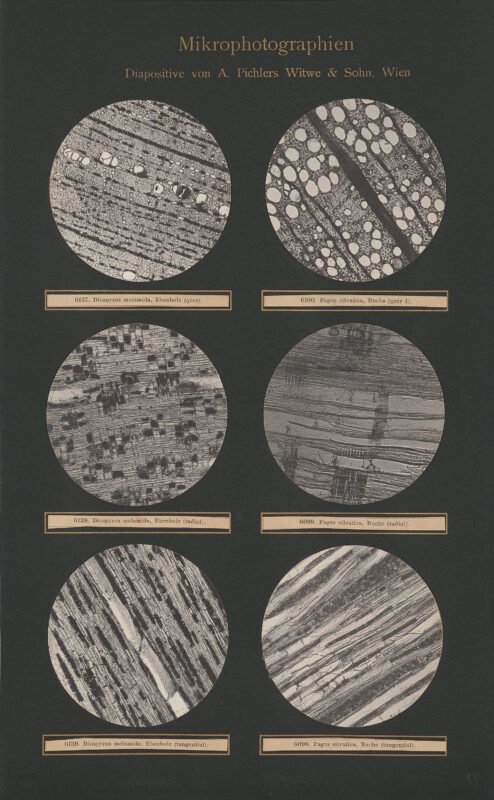

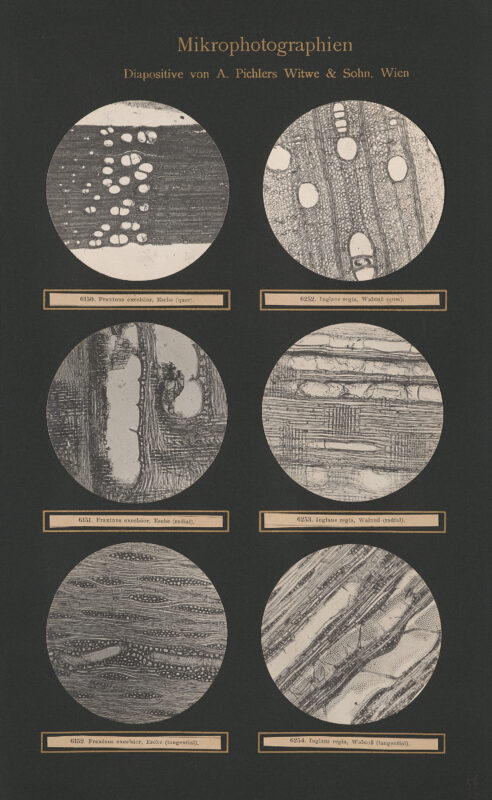

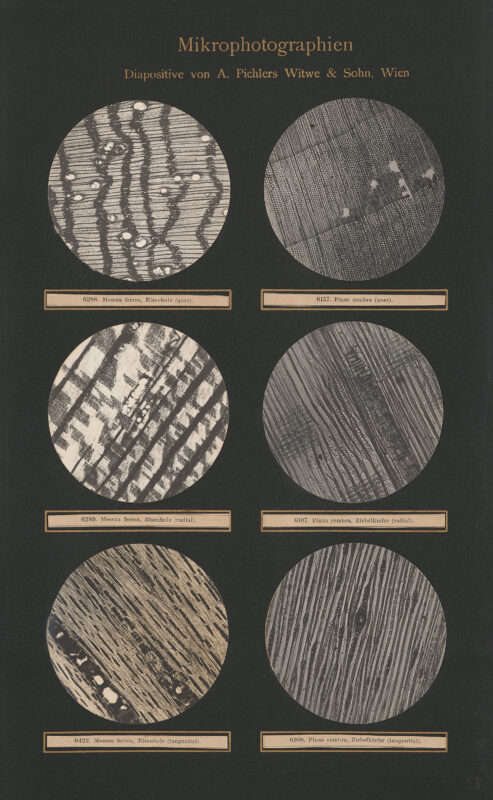

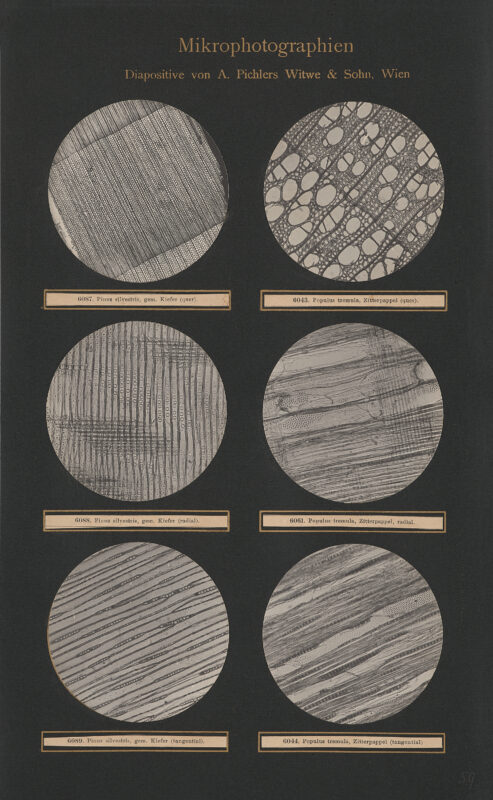

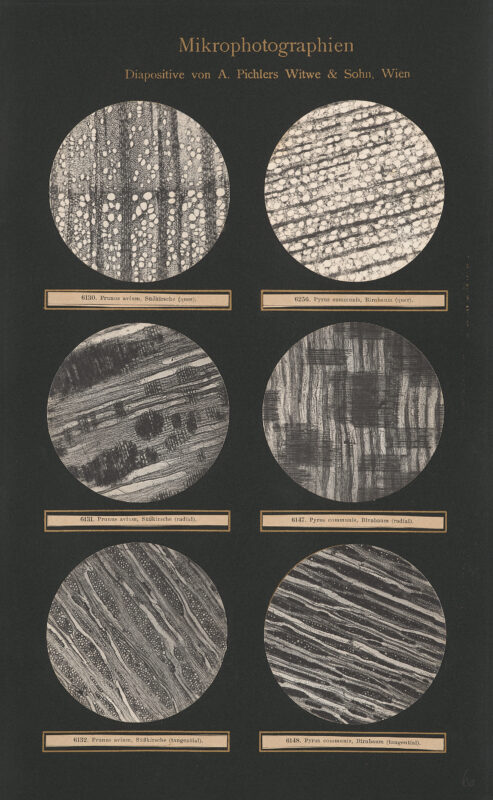

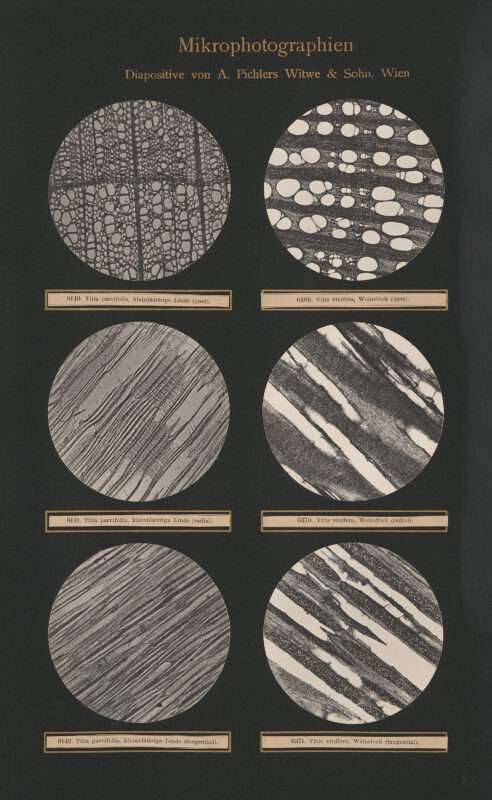

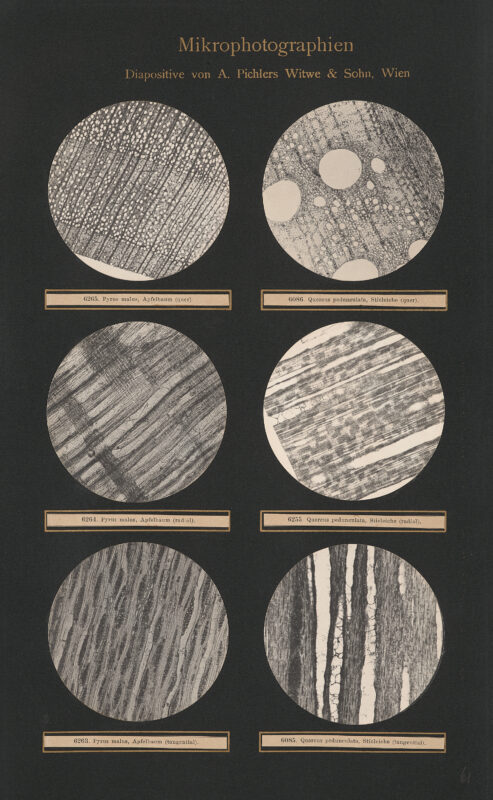

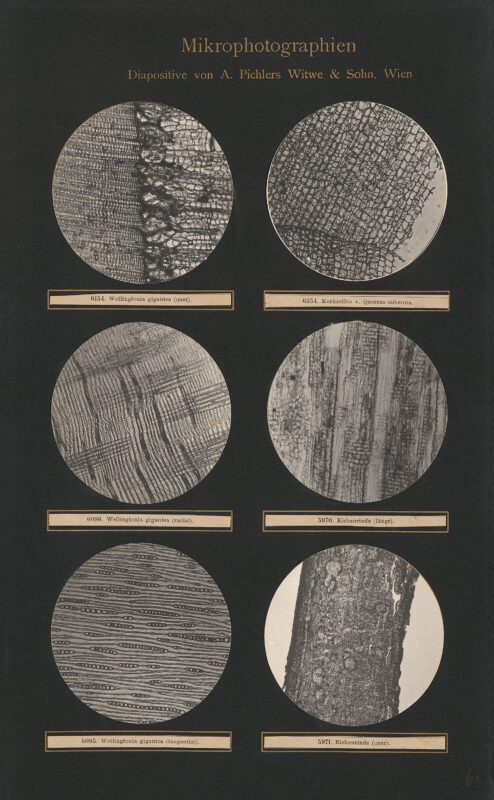

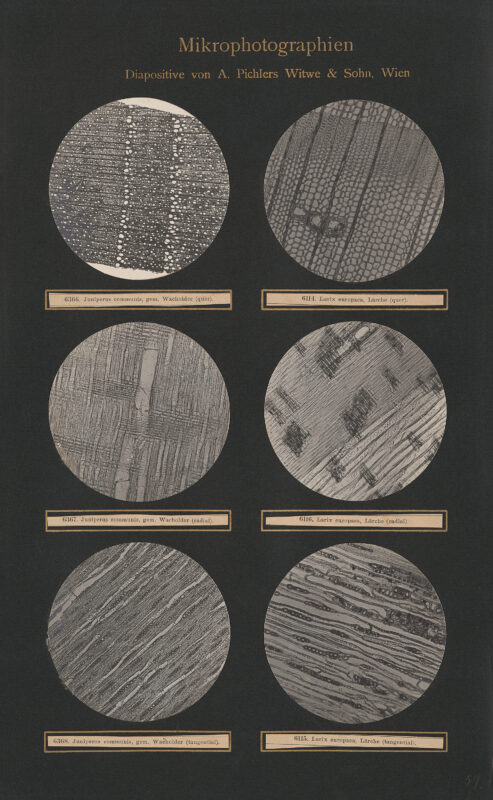

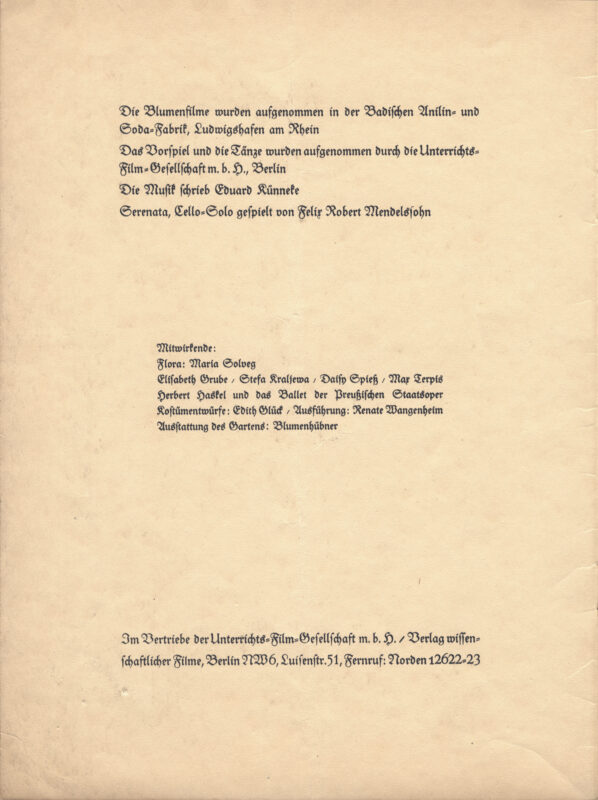

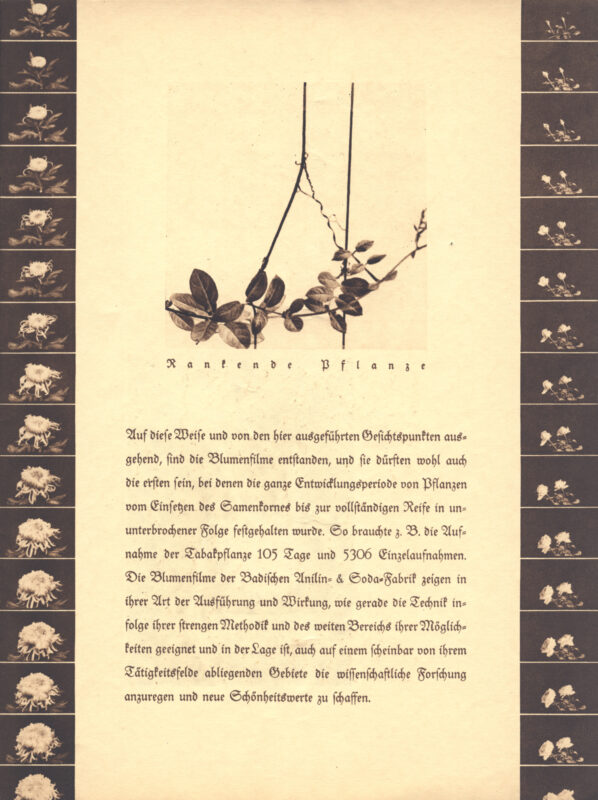

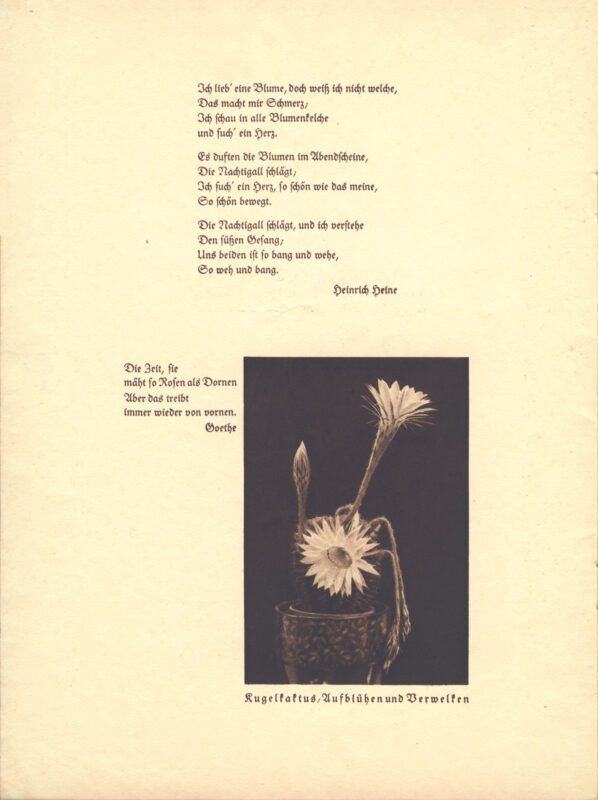

The Plant as a Relative

In 1920, books were still being published that contained statements such as, “Animals are living, but plants are not—that is the general opinion.” This view was radically shaken up by the introduction of time-lapse films of plants. In the nineteenth century, microscopic photographs had already revealed that humans, animals, and plants are all composed of cells. Studies of aquatic plants had also shown that plants produce the oxygen humans breathe. In the early twentieth century, the dividing line between humans and plants became less distinct, and the West experienced an early nonhuman turn. The writings of the Indian scientist Jagadish Chandra Bose enjoyed great popularity. In Plant Autographs and Their Revelations (1927), he observed: “In all this, we see how human-like is plant behaviour. In certain respects, the plant may even be found to be superhuman! I was awakened to this one day when taking a record of Mimosa in my laboratory. The response I was getting was uniform; but all of a sudden, there was a depression, for which I could at first discover no cause, since all the surrounding conditions appeared to be unchanged. On looking out of the window, however, I noticed a wisp of cloud passing across the sun. The plant had perceived the slight darkening which I had not noticed. As the cloud passed by, the plant recovered its normal exuberance, as the record show.” Philosopher Walter Benjamin described photography as a spewing source, a “geyser of new image-worlds,” and it was through these “image-worlds,” appearing in books, newspapers, and on cinema screens, that people began to rediscover plants in the 1920s.