Plant Sex

“Polymorphous Perversity” as Portal: On Lili Elbe, Plant Sex, and New Worlds

“The End of a World”

Within the rubble left behind by the coronavirus pandemic, many of us have found the carcass of one of the earliest mythologies enshrined as unimpeachable truth: humans are born to be autonomous, unburdened by the requirements of relationality. As the essentialness of systemically invisibilized people—nurses, meat and poultry workers, grocery store cashiers—became more evident, it became clearer that aliveness requires mutual care and reciprocal concern. “To be cared for,” says writer Anne Boyer, “is the invisible substructure of autonomy, the necessary work brought about by the weakness of a human body across the span of life.”[1]

During the first few months of the pandemic, when it felt as if the world was ending, I was reminded that to be human means to be in solidarity with and co-constituted by other humans—and those who inhabit spaces beyond humanness.

While receiving baked goods and care packages from friends, nesting with my partner, and scheduling digital gatherings with loved ones, I ignited a care-full relationship with plant life. Taking a cue from those in my life who were engaging in growing of all kinds—growing families through pregnancies, growing horizontal networks of mutual aid—I took up growing plants as an additional tool for weathering the course of global sickness.

My boyfriend and I introduced new houseplants to our burgeoning domestic ecosystem: a fragrant Vick’s plant and jalapeño peppers joined the windowsill; sprawling lavender and an assortment of herbs took up residency on our deck. We propagated Monsteras. Despite our amateur tending, a cold-weather garden of leafy greens, brussels sprouts, and autumnal flowers flourished. Vegetal life, as it always has for humanity, actively supported making our survival possible, providing medicine, food, oxygen, and beauty. Paraphrasing philosopher Emanuele Coccia, our plants began to garden us just as we gardened them.

Beyond material and affective offerings, our cadre of flora also beckoned us to consider whether the ways of humans, a death cult of profit-making and empire-building in which a disabling apocalypse incubated, are enough. They challenged us to ask whether the ways of humans are in need of a “species-scale betrayal,” as potently phrased by “aspirational cousin to all sentient beings” Alexis Pauline Gumbs.[2]

Why be needlessly urgent and chronically productive when you can unfurl in the sun, at your own pace, and know that being is all you must accomplish on any given day? What’s the use in conquering and extracting from another when you can revere your inherent interdependence with birds, bees, and soil, investing in the joy of being “kindred beyond taxonomy”?[3] How can you obliterate binaries and embrace a constellation of ways of showing up in the world, resisting, for instance, the endeavor of creating systems that only privilege succulents when succulents aren’t singular in their right to life? How can you reorient to just take what you need—nutrients, water—without hoarding what others may require? As I observed the plants around me—those in my home and those I encountered on walks around my neighborhood or during trips to the park—I found that how my botanic kin approached living critiqued human modes of existence. And that critique offered an invitation to a wholesale annihilation of the world as is. Plants gifted me a petition to walk through a portal into expanded manners of ordering life on Earth; they provided an instructive fuck you! to the ruinous logic of imperialist white-supremacist capitalist patriarchy.[4]

As I assumed the pandemic was bringing about the end of theworld, plant life assured me that the pandemic was only conjuring up space for the end of a world.

Tuning in to the frequency of plant epistemologies and those of other beyond-human entities—i.e., What can we learn from the ocean’s perspective? What could bacterial viewpoints press upon human futures?—feels like one of our most critical planetary health interventions. And it’s been critical across time. Within the ongoing dynamic of human life imprinting on plant life and plant life imprinting on human life, there’s a wellspring of possibility for exceeding the limits imposed on our bodies and the flesh of the world.

The life of Lili Elbe, full of entanglements with plants, comes to mind as a possibility model.

“Plants Throw the Nastiest Shade”

When you are all of the same thing, then you have to go to the fine point. In other words, if I’m a Black queen and you’re a Black queen, we can’t call each other “Black queens” because we’re both Black queens. That’s not a read—that’s just a fact. So then we talk about your ridiculous shape, your saggy face, your tacky clothes. Then reading became a developed form, where it became shade. Shade is, I don’t tell you you’re ugly, but I don’t have to tell you, because you know you’re ugly. And that’s shade.[5]

—American drag queen Dorian Corey in the 1990 documentary Paris is Burning

In the black-and-white photograph, we find two individuals—a man on the left, a woman on the right—nestled in what appears to be a bed of sand and fixed in poses that would feel right at home in Georges Seurat’s Un dimanche après-midi à l’île de la Grande Jatte (A Sunday on La Grande Jatte). Upon first glance, I can’t help but notice that the woman, the image’s lulling center of gravity, is serving face: her makeup is done with conscious care and acute motive. Her hair is coiffed, her hat is perched, her baubles are deliberately placed. The woman commands the camera to memorialize a moment rather than an offhand scene from a leisurely waterside jaunt. The detail that gives wind to the sails of her presentation is her dress: a sleeveless number awash in verdant, trailing, seemingly tropical vegetation on a lattice. The floral print, indexed as abundantly feminine across periods and cultures, becomes the woman’s accomplice in doing gender to a magnified degree.

The first line of the photograph’s caption elucidates that the shot is a portrait of Lili Elbe and “her friend” Claude Lejeune in interwar Europe. The second line—“(BEFORE THE OPERATION)”—timestamps the photo, situating it as an image captured before Elbe became the historical record’s first person to undergo a sequence of gender-affirming surgeries between 1930 and 1931. As described in the unpublished foreword attributed to Elbe for Fra Mand til Kvinde (From man into woman), a fictionalized account of Elbe’s life that has matured into a landmark transgender narrative, Elbe was the first person “not to be born unconsciously through their mother’s pangs but consciously through their own pain.”[6]

Now, the photograph of Elbe and Lejeune is a palimpsest: it concurrently is a memory fossilized by visual technology and a representation of a proto-self cultivated by Elbe. The snapshot as a whole comes to behave, pulling from Katie Sutton, as a series of “stepping stones toward another reality,” both “mediating and shaping” Elbe’s subjectivity.[7] The choice of dress, in particular, evolves into both a sartorial adoption of flora and a mobilizer of what plant life signifies among humans to help assemble Elbe’s gestating identity. A floral-clad Lili—who changed her family name to Elbe after the river in Germany, a “witness to her renaissance”—relies on the beyond-human realm in more ways than one to make real a world where a trans woman can get fabulous, lounge in the sun, and strike a pose for the camera.[8]

Clothing is integral to Elbe’s journey. She credited occasionally assuming “women’s clothing” and performing as a stand-in model for her ex-wife, Danish painter Gerda Wegener, as what led her to settle into her trans selfhood. In Mosaïques (Mosaics), the 1939 memoir by Elbe’s friend Hélène Allatini, a passage describes one of Elbe’s first public excursions as Lili and the use of attire by those in Elbe’s community to help corporealize her authenticity:

The weeks that followed were a dream come true for poor Lily: for her first outing, Gerda surprised her with a beautiful fur coat and then took her to the stores to choose everything that was still missing from her trousseau.[9]

The portrait of Elbe, a Danish trans woman assigned male at birth, and Lejeune calls to mind another image: a GIF of American multi-hyphenate artist Juliana Huxtable, who was born intersex and also determined to be male at birth (in 1987). The GIF’s looping frames preserve Huxtable’s response to an unseen interviewer asking, “What’s the nastiest shade you’ve ever thrown?” Her answer is curt but cutting: “Existing in the world.” Huxtable, an embodied disordering of a bifurcated gender system, raises up how living out gender opacity and living into a world where gender is boundless (or even an aside) is a dangerous affront—an eye roll, a sizing up, some nasty shade—to the dominant gender expectations of the West.

Just by being out in public, heliotropic, Elbe similarly throws her own shade, positioning the gender boundaries of her lifetime in her crosshairs. Also in the foreword of Fra Mand til Kvinde, Elbe uplifts how her existence is transgressive, to the point that she occupied a positionality that was entirely incomprehensible to the body politic of her time:

Within a society that is only accustomed to the normal, conventional and everyday things, I am the only being existing outside of any law, meaning not having previously been taken into consideration by any lawmakers.[10]

Elbe continues, observing how her journey was met with both admiration and pity as the global spotlight on her path-breaking transition ballooned:

My unique fate has been discussed in the newspapers of all countries and in all languages. They wrote about a miracle, yet, almost always, regarded me as a degenerate and sad creature.

Whoever did that was wrong.

Only those who have never seen me would speak about me like that. I am healthy, joyful and happy.

More venomous than Huxtable and Elbe combined, plants throw the nastiest shade of all. Before Elbe would mark a milestone in fracturing the foundation of an intrinsically fallacious and deleterious two-gender structure, fledgling explorations of plant life would reveal human approaches to living as inadequate, unimaginative, and violent—and would also play a hand in creating the loam from which Elbe would emerge.

“Vegetal Affections, Pleasures, and Desires”

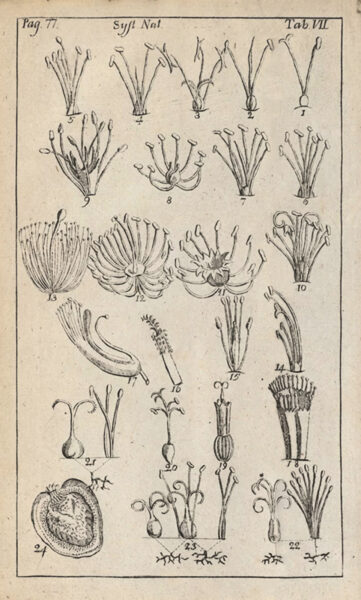

In the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, a colonialism-commerce-science braid became a vector for animating a Western wave of fascination with the lives of plants. This fascination held matters of vegetal sexuality at its center. Swedish taxonomic tastemaker Carl Linnaeus ascended as an authoritative architect of the era by introducing steamy schematics for cataloging plant life.

Linnaeus published Systema Naturae in 1735, proposing a system for classifying three kingdoms of the “natural world”: animals, minerals, and plants. In the flora-focused section of his text, Linnaeus locates his taxonomic model within imagined botanical boudoirs, unveiling an anthropomorphic “sexual system” driven by the concept of nuptiae plantarum, “the marriage of plants.”

The human-derived lexicon of heteronormative marital bliss populates Linnaeus’s organizing technology. Stamens transform into “husbands.” Pistils morph into “wives.” Floral anatomy becomes an erotic stage for vegetal consummation:

The flower’s leaves . . . serve as bridal beds which the creator has so gloriously arranged . . . and perfumed with so many soft scents that the bridegroom with his bride might there celebrate their nuptials with so much greater solemnity. When now the bed is so prepared, it is time for the bridegroom to embrace his beloved bride and offer her his gifts.[11]

Iterations of plant marriage, or the arrangements of husbands and wives, form the metrics by which classification occurs. Classes (representing the top rung of the system’s organizing ladder) are determined by the “number, relative proportions, and position” of stamens, while orders (representing the second rung of the ladder) are decided by referring to analogous criteria for pistils—gesturing toward an impulse to replicate patriarchal logics in the plant-centric system.[12] Simultaneously, the classifying principles undergirding the tool open the door for a diverse span of vegetal affections, pleasures, and desires to be articulated and documented, from the normative and familiar to the transgressive and illicit (at least from a human standpoint). Monandria is the name ascribed to a class of plants that engage in “monogamy.” Some plants commit to marriages where multiple—sometimes twenty—husbands are present. Within Linnaeus’s twenty-third class, Polygamia, we find “husbands and wives and unmarried individuals” who “cohabitate in several bridal chambers.”[13]

Even with its seeming ease of use, the tool is ultimately exposed as inadequate, as plants within the system refuse residency within hierarchies: Linnaeus’s twenty-fourth class, Cryptogamia, is comprised of mosses, lichens, ferns, and other plants participating in “clandestine” marriages or possessing sexual mechanics deemed illegible. Despite functional shortcomings originating from a botanic refusal of enclosure, Linnaeus’s invention narrates and lends conceivability to a “naturalized” spectrum of gender and sexual relations. With humanity being the starting point for representing that imaginative continuum, the Linnean system questions and brings into relief “how human sexuality might be organized, managed, and experienced differently.”[14]

As Linnaeus’s tool began to contribute to a lineage pinpointing new frameworks for human life in vegetal eroticism—and rose in popularity, obfuscating the existence of alternative systems established by his contemporaries—some followed Linnaeus’s lead while others wagged criticizing fingers. Erasmus Darwin, British physician, philosopher, naturalist, poet, and grandfather of Charles Darwin, published a two-part poem in 1789, The Botanic Garden, which adopted and pushed Linnean botanical metaphors to the edge. Several critics remarked upon the apparatus’s limited use and vulgarity; Johann Georg Siegesbeck, German botanist and staunch Linnaeus opponent, asked, “Who would have thought that bluebells and lilies and onions could be up to such immorality?”[15] Inherent to Seigesbeck’s question are emergent anxieties about what kind of human worlds “sexual indiscretion” among flora could birth. Maybe a world in which transness is normalized and quotidian?

Alongside plant life, queer zoological phenomena have also haunted and troubled rigid human categorizations. Within that history, German-Jewish doctor Magnus Hirschfeld—an influential researcher of sex, sexuality, and gender and a medical ally of Lili Elbe—is an illustrative figure.

A cornerstone of Hirschfeld’s body of work was demonstrating human expressions of “sexual intermediacy”—a term he coined to encapsulate the theory that “Geschlecht (sex/gender) can appear anywhere on a continuous scale between the opposing poles of male and female.”[16] In parallel intellectual tracks, a canon of scholarship dedicated to demystifying sexual and gender variance in the non-human animal sphere grew. German-Jewish geneticist Richard Benedict Goldschmidt found that he could establish “intergradations of male and female by mating different geographic varieties of the gypsy moth.”[17] Citing his experimental projects with guinea pigs and rats, Austrian physiologist and endocrinologist Eugen Steinach hypothesized that the “characteristics of sex could always be modified by modulating the functions of the sex glands,” suggesting a malleability in sexuality.[18] Bringing those and other threads of academic discourse in conversation with his sexological concerns, Hirschfeld argued that the human sexual and gender gradations he observed in his accumulation of autobiographical testimonies were mirrored in and, therefore, made biological by evidence of a sliding scale of sex, sexuality, and gender in Nature.

The suggestion that sexual and gender multiplicity are intrinsic to human and more-than-human existence energized Hirschfeld’s scholarly endeavors and political projects. An advocate for the rights of gender- and sex-variant communities (and believed to be a queer man himself, though never “out”), Hirschfeld leveraged burgeoning animal science and the “moral authority of nature” to debate that homosexuality, in particular, was an organic, natural variation of human experience.[19] With his deployment of animalian adjudicating forces, Hirschfeld agitated the legitimacy of Paragraph 175 of the German Imperial Penal Code, which criminalized male homosexual intimacies and characterized them as “unnatural” pathologies. Designating beyond-human animals as agents of social reform and tangible redress for persons marginalized by oppressive levers of powers, Hirschfeld reassessed the validity of the boundaries of his world, asking, Why should sexual and gender diversity overdetermine one’s access to full personhood and citizenship, and the rights annexed to those conditions, if a congruent diversity is found among our more-than-human kin?

From the histories of humans excavating the particularities of non-human animal sexual and gender dynamics and, as described by artist Adham Faramawy, the “polymorphous perversity, unimaginable to human beings,” among plants, a line is drawn to the possibility of Lili Elbe undergoing her transition.[20] In 1919, Hirschfeld opened the Institut für Sexualwissenschaft (Institute for Sexual Science), which provided several offerings, from guidance on marriage and contraception to counseling for those who, using contemporary terminology, identified as transgender. The Institute was also where Elbe was “interviewed, examined, and photographed before embarking on a series of [gender-affirming] surgeries.”[21] Caught up in a crucible of embryonic understandings of flora and fauna, Elbe found herself in relationship with people, ideas, and technologies that held space for and helped actualize expansive visions of human life that non-human beings prototyped.

Within this microhistory of Lili Elbe, it’s critical to foreground that decoding the fullness of human and extra-human lives does not begin or end with the labor of white men. The cosmologies of communities that are indigenous to diverse geographies of the planet include queer and trans presences alongside complex and lush “human-nature” enmeshments that long pre-date the spans of time discussed here. Relatedly, we can’t speak the names of the folks explored above without acknowledging the injury inflicted by their “discoveries.” Recent scrutinization of Carl Linnaeus’s legacy has found that his efforts set the table for scientific racism; Magnus Hirschfeld’s work walked hand-in-hand with regressive eugenicist aspirations. While bearing the potential to operate as a speculative space for working out pathways toward “progress,” Science, made in the image of human biases, is also a site of violence, erasure, and other consequences that continue to unfold today.

“Thrilling, Strange, and Eruptive Paths Forward”

Suppose botanical life can help engender the material conditions needed for a trans woman to self-actualize. How else could plant knowing help transform our world? That question isn’t rhetorical: I ask it with the utmost urgency, especially considering all that’s at stake for our global community. Bodies of water are on fire. Fascist momentum is mounting. Billionaires are multiplying and funneling their stolen spoils toward space races. At present, we are facing scales of violence that require the sum of our communities to reconsider the current contours of our lives so we can, as J. T. Roane elevates, “reclaim our intimacies from exploitation, our communities from cages, our cities from corporate takeovers, and our government from goons.”[22] Plants could serve as the compass we need to traverse the terrains of unnavigated human horizons.

Nothing about the way we do life is inevitable. How humans regulate and experience the world around us is forever fecund with opportunities to unsettle and disrupt, to regenerate and iterate. Just as plants have embraced their innate and infinite potentiality, shattering all that we know to be “natural” and absolute, we’re called to lean into the full capaciousness of what being human can mean, especially if we are to endure as a species. Independent scholar and artist Bl3ssing Oshun Ra reminds us that the Anthropocene, one of the names given to the culminating consequence of the forces that are the fulcrum of our current world, “is not ‘human’ (ie, rooted in homo sapiens, our species’ genetic code) but rather Man’s hand.”[23] “White supremacy,” they summarize with rapier precision, “is what is destabilizing the earth system, not ‘humanity.’” Before we lay total waste to ourselves and the planet, humans can choose thrilling, strange, and eruptive paths forward. With flora as blueprints, we can reassess which death-generating architectures to decompose to make room for life-giving expanses.

In a 1931 letter written to a friend, Lili Elbe vulnerably details her state of mind as she prepares for her final gender-affirming procedure—the one that is believed to have contributed to her death:

I am sitting out in the garden; but courage is a little scarce and so I must dash around among the bright birch trees; I know only too well what waits for me—and big abdominal operations are horrible, but I really do not think about dying at all; I do not have the permission to do that. It would be a betrayal.[24]

As I consider how plants may have allied with Elbe in helping her fashion herself, I imagine that the above scene showcases yet another moment in which botanic beings assisted her in moving toward who she was meant to be—in this case, by being attentive to Elbe’s emotional and psychic wellbeing. Sitting among my own collective of plants, I also imagine how the vegetal world can guide the totality of humanity in moving fearlessly toward who we’ve always needed to be: molten, slippery, evading the borders of our own making.

Selected Bibliography

- Barrett, Spencer C. H. “Understanding plant reproductive diversity.” Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B (2010).

- Bull, Jacob, and Margaretha Fahlgren. Illdisciplined Gender: Engaging Questions of Nature/Culture and Transgressive Encounters. New York: Springer International Publishing, 2016.

- Castro, Teresa. “The Mediated Plant.” e-flux Journal, September, 2019. http://www.e-flux.com/journal/102/283819/the-mediated-plant/.

- Cornish, Caroline. “Sentience and Sensibility: A Selective History of Plant-Human Perceptions.” The Philosophical Life of Plants. http://www.plantphilosophy.org.uk/histories-of-plant-thinking/sentience-and-sensibility-a-selective-history-of-plant-human-perceptions/.

- Encyclopaedia Britannica Online, s.v. “Lili Elbe,” by Naomi Blumberg, 2021. http://www.britannica.com/biography/Lili-Elbe.

- Erickson, Bruce, and Catriona Mortimer-Sandilands. Queer Ecologies: Sex, Nature, Politics, Desire. Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 2010.

- Flemming, Rebecca, Nick Hopwood, and Lauren Kassell, eds. Reproduction: Antiquity to the Present Day. Cambridge: University of Cambridge, 2018.

- Haney, David H. When Modern Was Green: Life and Work of Landscape Architect Leberecht Migge. New York: Routledge, 2010.

- Jacobs, Joela. “Phytopoetics: Upending the Passive Paradigm with Vegetal Violence and Eroticism.” Catalyst 5, no. 2 (2019).

- Moore, Lisa L. “Queer Gardens: Mary Delany’s Flowers and Friendships.” Eighteenth-Century Studies 39, no. 1 (2005).

- Moore, Randy. “Linnaeus & the Sex Lives of Plants.” The American Biology Teacher 59, no. 3 (1997).

- New York Botanical Garden, “Queering Botanical Science: A Discussion in Celebration of LGBTQ+ Pride Month,” New York, 2020. http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=INWLzfkMCEU.

- Russell, Legacy. Glitch Feminism: A Manifesto. New York: Verso, 2020.

- Sandilands, Catriona. “Botanically Queer.” Presentation at The Society of Fellows and Heyman Center for the Humanities, New York, 2014. http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=bdoFZQNrlM0.

- Schillace, Brandy. “The Forgotten History of the World’s First Trans Clinic.” Scientific American, May 10, 2021. http://www.scientificamerican.com/article/the-forgotten-history-of-the-worlds-first-trans-clinic/.

- Sutton, Katie. “‘We Too Deserve a Place in the Sun’: The Politics of Transvestite Identity in Weimar Germany.” German Studies Review 35, no. 2 (May 2012).

- Terry, Jennifer. “‘Unnatural Acts’ in Nature: The Scientific Fascination with Queer Animals,” GLQ: A Journal of Lesbian and Gay Studies 6, no. 2 (2000).

- United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, s.v. “Magnus Hirschfeld.” http://encyclopedia.ushmm.org/content/en/article/magnus-hirschfeld-2.

- University of California Museum of Paleontology’s, s.v. “Carl Linnaeus.” https://ucmp.berkeley.edu/history/linnaeus.html.

- Uppsala Universitet. “Linnaeus Sexual System.” http://www.linnaeus.uu.se/online/animal/2_1.html.

- ↑ Anne Boyer, The Undying: Pain, Vulnerability, Mortality, Medicine, Art, Time, Dreams, Data, Exhaustion, Cancer, and Care (New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2019), 125.

- ↑ Alexis Pauline Gumbs, Dub: Finding Ceremony (Durham: Duke University Press, 2020), x; Alexis Pauline Gumbs, the “About” page. Online: www.alexispauline.com/about.

- ↑ Alexis Pauline Gumbs, Dub: Finding Ceremony, xii.

- ↑ I’m grateful for writer, activist, and cultural critic bell hooks gifting us the phrase “imperialist white supremacist capitalist patriarchy,” which crucially presents the oppressive forces that govern so many of our lives as a multi-headed assemblage.

- ↑ starkeymonster, “Dorien Corey on throwing shade” (2011), clip from the documentary Paris is Burning, directed by Jennie Livingston (1990). Online: www.youtube.com/watch?v=Z2lEtUqxg44.

- ↑ Lili Elbe, Fra Mand til Kvinde, trans. Tatjana Willms-Jones (2020), Lili Elbe Digital Archive, ed. Pamela L. Caughie, Emily Datskou, Sabine Meyer, Rebecca J. Parker, and Nikolaus Wasmoen, 1. Online: http://www.lilielbe.org.

- ↑ Katie Sutton, “Sexology’s Photographic Turn: Visualizing Trans Identity in Interwar Germany,” Journal of the History of Sexuality 27, no. 3 (September 2018), 474–75.

- ↑ Hélène Allatini, Mosaïques, trans. Anne M. Callahan, Lili Elbe Digital Archive (2020), 227.

- ↑ Allatini, Mosaïques, 221.

- ↑ Lili Elbe, Fra Mand til Kvinde, 2.

- ↑ Martin Kemp, Visualizations: The Nature Book of Art and Science (Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press, 2000), 49.

- ↑ Londa Schiebinger, Nature’s Body: Gender in the Making of Modern Science (New Brunswick: Rutgers University Press, 2004), 14.

- ↑ Jacob Bull and Margaretha Fahlgren, Illdisciplined Gender: Engaging Questions of Nature/Culture and Transgressive Encounters (New York: Springer International Publishing, 2016), 121.

- ↑ Natania Meeker, “Thinking about Sex with Plants,” The Philosophical Life of Plants. Online: www.plantphilosophy.org.uk/histories-of-plant-thinking/thinking-about-sex-with-plants/.

- ↑ Kennedy Warne, “Organization Man,” Smithsonian Magazine, May 2007. Online: www.smithsonianmag.com/science-nature/organization-man-151908042/.

- ↑ Ina Linge, “The potency of the butterfly: The reception of Richard B. Goldschmidt’s animal experiments in German sexology around 1920,” History of the Human Sciences 34, no. 1 (2021): 41. Until the early twentieth century, those spearheading sexological pursuits placed trans and same-sex embodiments under one umbrella. After, new language developed to specifically refer to what are currently understood as transgender experiences, including Hirschfeld’s Transvestit/in (transvestite) and Transvestismus (transvestitism).

- ↑ Michael R. Dietrich, “Of Moths and Men: Theo Lang and the Persistence of Richard Goldschmidt’s Theory of Homosexuality, 1916–1960,” History and Philosophy of the Life Sciences 22, no. 2 (2000): 220.

- ↑ Chandak Sengoopta, The Most Secret Quintessence of Life: Sex, Glands, and Hormones, 1850–1950 (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2006), 65.

- ↑ Hirschfeld was also known for assisting individuals with receiving “transvestite certificates” or “passports,” which permitted holders to publicly dress in a manner that aligned with their gender identity without fear of being arrested. Against the backdrop of Germany’s progressive Weimar era, the provision of “transvestite certificates” and “passports” coincided with the early formation of a unified “transvestite” voice and identity.

- ↑ Adham Faramawy, interview by Kostas Stasinopoulos, “Skin Flick,” Vdrome, 2019. Online: www.vdrome.org/adham-faramawy/. This language echoes Freud’s concept that young children investigate “polymorphous” erotic scenarios before being indoctrinated into belief systems that differentiate between what’s “acceptable” and what’s “perverse.”

- ↑ Emily Datskou et al., “Publication History,” Lili Elbe Digital Archive, 2020. Online: www.lilielbe.org/narrative/publicationHistory.html. In the twentieth century, the sexological field began to migrate from anchoring scientific evidence in collected lived experiences to locating “truth” in photography; the pivot sought to provide more credibility to a still marginal area of study. The visualization of sexology begot an archive of trans portraiture in the sciences—an archive that both left photographed individuals bereft of interiority via the “medical gaze” and provided subjects with the opportunity to actively participate in acts of intentional self-making. This photographic shift overlapped with a rise in visual media (e.g., German filmmaker Max Reichmann’s 1926 Das Blumenwunder [The Miracle of Flowers] and Indian plant physiologist and physicist Sir Jagadish Chandra Bose’s plant autographs) intervening to widen humanity’s ocular nets to recognize plant life as comprised of elements thought to only be possessed by humans and other animals. Both histories signpost visuality as a conductor of renegotiating human ontology.

- ↑ James T. Roane, “Courting the End of the World: Heeding James Baldwin’s Invitation to take up a Dangerous Morality,” Brooklyn Rail, October 2016. Online: www.brooklynrail.org/2016/10/criticspage/courting-the-end-of-the-world.

- ↑ K. D. Wilson, “Who’s Man is This? Black Radical Ecology and the Anthropogenic Question,” Red Voice, 2020. Online: www.redvoice.news/black_radical_ecology_and_the_anthropogenic_question/.

- ↑ Lili Elbe, 1931-06-16 Letter to Maria Garland from Lili Elbe, Lili Elbe Digital Archive, 2020. Online: www.lilielbe.org/context/letters/1931-06-16ElbeGarland.html.